An old, grainy video depicts a group of African American schoolchildren holding hands as they skip in a circle. In the middle of this circle is a young African American boy in a loose white shirt and black pants. Suddenly, the children stop skipping and begin clapping at the same moment that the boy in the center breaks out in dance. We watch as he shows off his impressive and energetic moves such as cartwheels and the splits. This short film, produced in 1928 and titled Children’s Game, was filmed by Zora Neale Hurston, a very famous and influential African American anthropologist and writer. [11]

Zora Neale Hurston was born January 15th, 1891 in Notasulga, Alabama to parents that had both been previously enslaved. Soon after, she and her family moved to Eatonville, Florida, where she resided until attending Howard University. Here, she was a very active student, joining the student government and co-founding The Hilltop, a popular newspaper at Howard. She then received a scholarship to study at Barnard College at Colombia University, where she received a Bachelor of Arts degree in anthropology. Here, she met other writers such as Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen, whom she would go on with to contribute to the Harlem Renaissance, a period defined by the explosion of African American culture in Harlem, New York. Although Hurston is most well known for her contributions to the Harlem Renaissance and writings such as Their Eyes Were Watching God, she also contributed significantly through her anthropological and ethnographic research, such as the film mentioned above.

During her time at Howard University, Hurston first found an interest in anthropology by observing how different the students there were in comparison to the people in her hometown, whom she had been surrounded by practically her entire life. She greatly furthered these interests at Columbia University, where she worked with the man sometimes referred to as the father of American anthropology, Franz Boas. Boas took a special effort to encourage his students to deeply immerse themselves into the cultures and communities in which they chose to study. With this in mind,

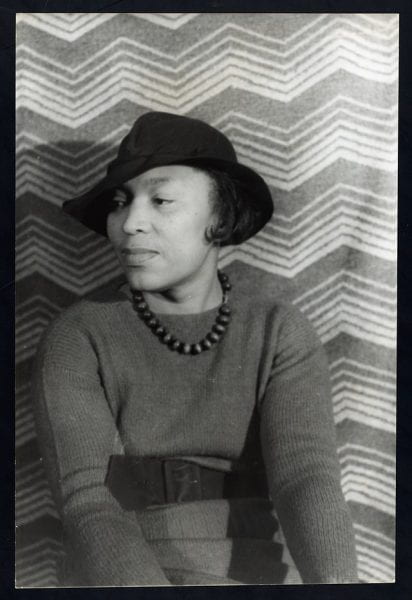

Zora Neale Hurston, 1938. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Hurston dedicated many of her early years of anthropology to the study of hoodoo. [2] Hoodoo, a set of spiritual practices, traditions, and beliefs created by enslaved Africans and hidden from slave owners, originated in the American south and later spread across the United States during the Great Migration (which was also a significant cause of the Harlem Renaissance). In order to study hoodoo, she returned to her hometown of Eaton, Florida. Here she dove deep into the study of hoodoo by fully immersing herself through experience. Hurston wrote to Alain Locke, an advisor and former professor at Howard University, that “for the sake of thoroughness, [she was] using the vacuum method; grabbing everything [she could] see.” Hurston said she was meeting with every single hoodoo doctor she ever heard of, leaving no stone unturned or ritual unexperienced. In 1935, Hurston wrote Mules and Men which was a collection of African American culture and folklore she had experienced during her trips to North Florida. In an excerpt, she describes her experience of going without food or water for sixty-nine hours straight as part of a hoodoo ritual. In great detail, she described being “stretched, face downwards [on top] the snakeskin cover, and began [her] three day search for the spirit [in which she] could have no food, but a pitcher of water” [3]. This intense description is one of her experiences with a local hoodoo doctor Luke Turner. As seen in the excerpt above, Hurston not only studied and researched hoodoo as a spiritual practice but deeply immersed herself in the culture as a whole, experiencing it as any other hoodoo participant would. Above is one of the many unique experiences she put herself through to understand other cultures. Again with the guidance of Luke Turner, Hurston participated in confessions, similar to those of Catholicism but required her participation in the sacrificing of chickens. She gathered the chickens, helped kill them, and spread the ashes on a highway to help a woman who wished to get rid of her husband’s brother. The ashes were supposed to be a barrier to stop the brother from returning. With another hoodoo doctor, Hurston gathered a beef brain, beef tongue, a beef heart, a black cat, and a live black chicken in addition to a small doll that resembled a man that someone hoped would die. According to Hurston, the desired death of the man occurred, as expected, during the ritual process. Without judgment of doubt, Hurston went through many unconventional and uncomfortable experiences to truly examine the culture and lives of others. She allowed herself to portray these cultures in their truest forms by intimately experiencing them firsthand. [4]

As mentioned above, Zora Neale Hurston also produced several films and videos despite mostly being known for her work as a journalist. Although not certainly known, there is a good possibility that Hurston may have been the first black female filmmaker, adding another barrier she destroyed to her accomplishments. These videos, such as Children’s Game, depicted the everyday and real lives of African Americans in the American south. Being a primary source, her videos added another layer of authenticity to her anthropological research. [11] Although still underappreciated, her seemingly most well known movie was about Cudjo Lewis, a member of a very large family in West Africa. West Africa. Like many before him, Cudjo, known at birth by “Kossola”, was captured by an African army and then brought to a slave shipping port to be sent to the United States of America on a ship called the Clotilde. However, being captured in 1860, the transportation and sale of slaves from Africa was illegal, however, the Clotilde snuck across the ocean and into the United States to sell slaves and is considered the last ship to ever carry slaves to the States. After the end of slavery in 1868, Cudjo and many of the other slaves on the Clotilde hoped to save up enough money for the voyage back to Africa, however, with the economic opportunities available to African Americans at the time, this was next to impossible. Instead, they formed their own community, known to outsiders as Africantown, where they spoke their native African language rather than English. Here, African culture was able to flourish and persist despite outside influences. [6]

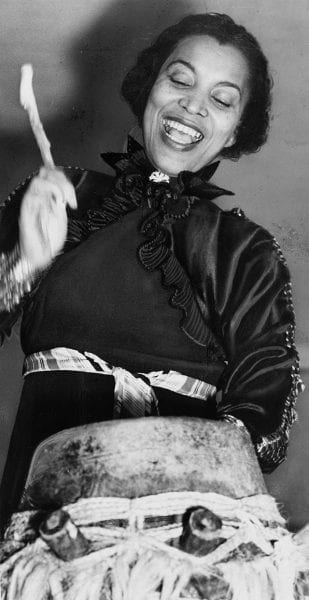

Zora Neale Hurston, beating the hountar, or mama drum, 1937. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

When Zora Neale Hurston met and interviewed Cudjo, he was the last surviving member of the group forcefully taken on the Clotilde. However, she was able to preserve not only Cudjo’s story but also his fellow Africantown members’. Her film of Cudjo still exists to this day as a uniquely accurate representation of the past. She first wrote about Cudjo in her Journal of Negro History, also she continued to make more trips to visit, learn from and interview this survivor. The forceful relocation of African people was of course often accompanied by a complete disregard for any culture and pressured enslaved people into American culture. Cudjo, through the founding of Africantown, managed to resist the strong forces of cultural genocide. Similarly to Cudjo, Zora Neale Hurston was able to further combat cultural genocide through her accurate depictions of these people and their cultures. Although her films were limited and never became widespread, they still preserve a true account of the lives of these marginalized people. [7]

As previously mentioned, Hurston’s most-talked-about influence comes from her writings and leadership during the Harlem Renaissance. In 1930, she worked with Langston Hughes to create The Mule Bone: A Comedy of Negro Life In Three Acts, which was a play for African-American actors that wouldn’t use racial stereotypes. Despite its lack of immediate success and recognition, she made a second play of the same type, The Great Day, which managed to get itself on Broadway. Furthermore, she and a few other African-American writers started the literary magazine Fire!!, which very controversially discussed issues of homosexuality, bisexuality, interracial relationships, promiscuity, prostitution, and color prejudice. Being incredibly controversial, Fire!! lacked in sales and received a ton of negative responses but Hurston, seeing it as a force for the greater good, continued to break societal norms with this magazine. [8] In the coming years, Hurston wrote the majority of her novels including her few most successful ones. She implemented many of the ideas she had picked up through her experiences and studies to promote cultural ideas through her writing. Yet a couple of years later (in 1938), Hurston fully returned to the field of anthropological studies with Tell my Horse, another account of her first-hand hoodoo experiences. Even at the height of her literary career, Hurston decided to return to anthropology.

Despite, all her success as a novelist, Hurston continued to dedicate her life to anthropology until she, unfortunately, passed away penniless and under-appreciated. [9] In doing so, she truly proved her dedication to anthropology and the cultures she chose to study. She was a voice for the unspoken. She documented these cultures that were never professionally studied, allowing them to be preserved today in a form true to themselves. She was a true anthropologist.

About the Author:

Will is a second year student currently studying at the University of Chicago. He is pursuing a major in both Computer Science and Business Economics as well as exploring a variety of academic interests.

Reference:

Featured Image: Zora Neale Hurston. Courtesy of The Public Broadcasting Service.

- Tikkanen, Amy. “Zora Neale Hurston.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/biography/Zora-Neale-Hurston.

- Rutsch, Poncie. “Novelist Zora Neale Hurston Was a Cultural Anthropologist First.” WHYY, WHYY, 18 Mar. 2017, https://whyy.org/segments/novelist-zora-neale-hurston-was-a-cultural-anthropologist-first/.

- Hurston, Zora Neale. Mules and Men, Harper Perennial, New York, New York, 2008, p. 199.

- Admin. “Zora and the Hunt for Hoodoo in New Orleans.” Deep South Magazine, 4 Mar. 2016, https://deepsouthmag.com/2015/05/07/zora-and-the-hunt-for-hoodoo-in-new-orleans/.

- Zora Neale Hurston. Columbia University, https://wfpp.columbia.edu/pioneer/zora-neale-hurston/.

- Kuroski, John. “The Story of Cudjo Lewis – The Last Living Slave Brought To America .” All That Is Interesting, 8 Dec. 2017, https://allthatsinteresting.com/cudjo-lewis.

- Cep, Casey, et al. “Zora Neale Hurston’s Story of a Former Slave Finally Comes to Print.” The New Yorker, 7 May 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/05/14/zora-neale-hurstons-story-of-a-former-slave-finally-comes-to-print.

- Lehoczky, Etelka. “Elastic Lines for an Elastic Life in ‘Fire!!’.” NPR, NPR, 22 Mar. 2017, https://www.npr.org/2017/03/22/515438118/elastic-lines-for-an-elastic-life-in-fire.

- “Zora Neale Hurston, Genius of the Harlem Renaissance.” Mental Floss, 7 Jan. 2019, https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/73895/retrobituaries-zora-neale-hurston-genius-harlem-renaissance.

- “Zora Neale Hurston Biography.” Encyclopedia of World Biography, Advemeg, https://www.notablebiographies.com/Ho-Jo/Hurston-Zora-Neale.html.

Video:

- Powell, Azizi. “1928 Film Clip of Black Children’s Circle (Ring) Games.” 1928 Film Clip Of Black Children’s Circle (Ring) Games, 1 Jan. 1970, http://pancocojams.blogspot.com/2017/03/heres-fantastic-find-1928-film-clip-of.html.