Jane Jacobs was an urban theorist and writer, born in 1916 and died in 2006, who thought about the way that urban organization impacts city life and social issues. One of the most influential figures in pivoting the conversation of urban studies away

from the urban-renewal focus of the 1960s, her writing covers topics from the built environment to the future of democracy. Her main and most famous contribution to social science was her understanding of cities as complex systems that require diversity and gradual change. Jacobs championed the notion of a dynamic city network in which changes should be responsive to the pre-existing life of the city.

Although Jacobs contributed greatly to urban theory, her recognition was originally lessened and complicated by her lack of formal education. She was an urbanist, ecologist, geographer, economist, and sociologist, among many other titles. But because of her lack of formal training and her unorthodox career, she was often looked at solely as a housewife with a bit of spare time on her hands. Peter L. Laurence, in his 2016 biography of Jacobs, Becoming Jane Jacobs, wrote that she was “primarily a housewife with unusual abilities to observe and defend the domestic surroundings.”[1] Rather than being regarded as a professional writer or theorist, Jacobs gained notoriety as a “housewife” who expressed interesting observations about her immediate environment. Jacobs never received any degrees from higher education. She only had a high school diploma when she moved to New York City and only attended a few classes on economic geography at Columbia’s extension program. In New York City, she worked as a freelance journalist. Because her work experience is primarily in writing, Jacobs developed a unique writing voice that could effectively persuade readers of her ideas in a compelling narrative.

I take issue with Laurence’s description of Jacobs as a housewife who only remained in the domestic sphere because Jacobs greatly contributed to urban theory, however, his note about her knack for and “unusual abilities to observe” are quite accurate. Jacobs self-trained her journalistic eye to discern important elements of city life. Her method to understanding cities was founded on observation and real life experience. Jacobs is well known for her sidewalk observations, where she would describe the activity on a city block or follow the patterns of movement around city sidewalks. She had a keen eye for noticing what drove the life of a city, and this style of observation is what led to her first truly recognized work: an essay called “Downtown is for People” published in Fortune Magazine in 1958. In “Downtown is for People,” Jacobs writes “You’ve got to get out and walk. Walk, and you will see that many of the assumptions on which the projects depend are visibly wrong.” Jacobs encourages people to employ the same kind of observational tactic she has to understand her points. This essay and much of her other important work was largely in response to her theoretical and policy context: the “projects” of urban planning at the time.

Jane Jacobs holds up documentary evidence at press conference at Lions Head Restaurant. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Modernist urban planning in the 1960s rested on the belief that the best cities were created when old features were destroyed in favor of new. One icon of 20th century urban planning who had an immense amount of influence in New York City particularly was Robert Moses, an urban planner and highway engineer. Moses’ work centered on planning around the automobile experience and the complete renewal of city areas. He was in favor of the replacement of historic neighborhoods with planned and controlled housing projects. This kind of urban planning would often segment urban space by highways, prioritizing the experience of cars over the experience of pedestrians. Jacobs’ work responded to the kind of urban planning championed by Moses. In “Downtown is for People,” Jacobs expresses some of her initial considerations on city life. She argues that cities should be for people, rather than planned around economic or industrial infrastructure. She responds to modernist planners and discusses what truly makes a city lively.

Jacobs disagreed with the strategies and theory of modernist urban planning. She believed that urban planners at the time worked with too much of a top-down approach. Urban planners would go into an area and start from scratch, imposing highways or standardized apartment buildings. In “Downtown is for People,” Jacobs critiques urban planning by calling their designs destructive to the individuality and character of different cities. She claims that “these projects will not revitalize downtown; they will deaden it. For they work at cross-purposes to the city. They banish the street. They banish its function. They banish its variety.” Jacobs believed that urban planners should instead look at what was already in the city and work off of that when considering improvements to be made. She found this kind of planning too simplistic and too statistical; she believed it took a great deal of life away from the city. Figures like Moses, according to Jacobs, had the wrong way of thinking about what makes a good city. Instead, Jacobs advocated for urban theorists to observe the actual life of a city, “see what people like,” and respond accordingly.

She opposed modernist urban planning in theory, but also in practice with her activism. In 1968, there was a proposal to build an expressway through Lower Manhattan. This expressway would have gone through Washington Square Park and destroyed much of Soho. Robert Moses was the city planner in charge of the expressway. Jacobs worked in Greenwich Village at the time and did not want her neighborhood to be destroyed in favor of highways. Jacobs wrote to the mayor, coordinated with the save the park committee, got a hold of media outlets such as Village Voice, and organized her community. Over what ended up taking several years, she ultimately helped save her neighborhood from being wrecked by an unnecessary highway.

Jacobs was not a conservative, in fact she strongly believed in the importance of improving city life and recognizing its dynamism; she just championed a different kind of change than her contemporaries. She felt that cities should grow according to the needs of the life and activity that already exists there. Both the modernist planning at the time and Jacobs’ views on cities encouraged urban change and growth—but Jacobs’ picture of change was more grassroots and neighborhood oriented. She valued being responsive to the existing city rather than the imposition of a regimented plan that does not truly understand the area. Jacobs thought that local knowledge was most important in urban planning so that change can develop off an existing foundation of life. She wrote in The Death and Life of Great American Cities that “lively, diverse, intense cities contain the seeds of their own regeneration, with energy enough to carry over for problems and needs outside themselves” (585). Jacobs wanted urban planners to stop prescribing measurements and plans to cities and instead to listen to the needs of the city on a more localized level and respond accordingly. Her own method for understanding cities, based on sidewalk observations grounded in real experience, complemented these ideas about how a city should change and grow in a responsive way. She outlined this in “Downtown is for People,” and expanded on these concepts in her The Death and Life of Great American Cities which she published in 1961.

The Death and Life of Great American Cities is arguably Jacobs’ most influential work. In it, Jacobs outlines what ultimately became the major tenets of modern day urban studies and design, solidifying herself as a defining voice of the field. Jacobs examines how to think about cities and how to make them better in this book. When discussing the way to think about cities, Jacobs emphasizes the complexity of city networks. She often expresses this idea through similes emerging from her sidewalk observations. All of Jacobs’ writing is stylistic and compelling, complementing her keen observation, to make her a distinct and unique original thinker. The Death and Life of Great American Cities is characterized by complex analogies that paint a vivid picture of city life in order to convey her understanding of the social issues of cities. Jacobs compares cities to fabric, in which each thread is inextricable from the other. She also compares sidewalks to an intricate ballet, in which every dancer has a unique role but they all come together in a complex performance. With these analogies, Jacobs demonstrated the danger of changing one aspect of the city without its context.

Jane Jacobs with environmentalist Spencer Beebe, 2004. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs also outlined elements of what makes a city function well. She noted the importance of higher density, shorter blocks, strong local economy, and walkable communities (which was a significant challenge to the car centered approach of urban planning at the time). She also argued for the importance of diversity—of city block usage, people, government, transportation, and architectural style. In advocating for the development of these particular variables, she always thought about how they fit in with each other. For example, she understood the way that transportation impacts mobility. In this book, Jacobs changed the discussion about cities, shifting the conversation from the imposition of urban planning without much local knowledge to a responsive, localized acknowledgement of the complexity of the urban makeup.

Aside from The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs published seven major works on urban theory, economics, the importance of cities to the development of countries, and the life and decline of democracy. Jacobs’ lifework had a huge influence on the entire field of urban studies. New Urbanism, a movement that developed in the 1980s, adopted Jacobs’ prioritization of walkable, environmentally friendly communities. Jacobs is widely read as a primary text in architecture or urban studies courses, and she also influenced community planning and activism. Jacobs’ position as an urbanist, thinker, and writer makes it difficult to place her in one category of profession. This inability to categorize her is arguably what makes her so special, as the act of placing aspects of life into categories is just not how she thought about the world. She did not view the world in binaries. In Blake Harris’ interview with Jane Jacobs, Harris asks Jacobs if she thinks people are confused about why she had recently been writing about economic and biological theories if her main focus has been on urban planning. Jacobs responds by saying:

You know, I think we are misled by universities and other formal intellectual places into thinking that there are actually separate fields of knowledge…[people] are delighted when in some respectable way it becomes clear that there are not separate fields of knowledge, that they link up. That life and the Earth and everything in it really is a seamless web, and that’s not merely a poetic expression. It is a very functional thing, that it is a seamless web, and that it is possible to understand something about these webs.

Jacobs was somehow able to sort through and recognize the importance of life as a “seamless web,” an intricate and complicated system that people can understand by experiencing first hand. She applied this perspective on life to each of her works and because she was freed of academic constraints, she was able to reframe how to look at the life of cities without constraint as well. Always emphasizing the intricacy of life, Jacobs valued building systems off of existing structures to establish better functioning urban spaces that reflect the real and complex lives of the people already there.

About the Author:

Tatiana Jackson-Saitz is a second year from Boston, majoring in English Language & Literature and Environmental & Urban Studies.

References:

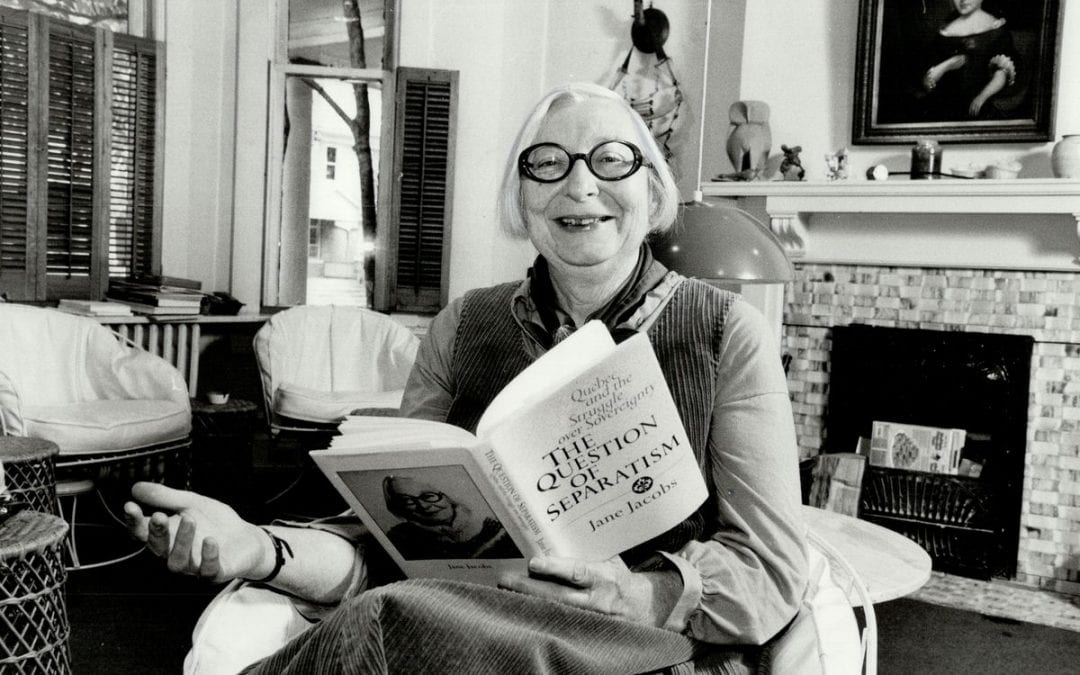

Featured Image: Jane Jacobs. Source: Vox.com 2016

Chantry, Erin. “Urban Designer Series: Robert Moses,” Smart Cities Dive. Web. https://www.smartcitiesd ive.com/ex/sustainablecitiescollective/urban-designer-series-robert-moses/54826/

Harris, Blake and Jane Jacobs.“Interview: The Trouble We’re In, and the Changes to Come.” Essays on Jane Jacobs. Bokforlaget Stolpe AB, 2020.

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Vintage Books, 1961.

Jacobs, Jane. “Downtown Is for People.” Fortune, 1958. https://search-ebscohost-com.proxy.uchicago.edu /login.aspx?direct=true&db=fma&AN=112500144&site=eds-live&scope=site

“Jane Jacobs,” Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jane-Jacobs

Rich, Nathaniel. “The Prophecies of Jane Jacobs,” The Atlantic, November, 2016. https://www.theatlantic. com/magazine/archive/2016/11/the-prophecies-of-jane-jacobs/501104/

Carlson, Eric. “How Jane Jacobs Fought The Destruction of New York City’s SOHO Neighborhood,” May, 2020. https://medium.com/modern-city/how-jane-jacobs-fought-highway-development-35 1a9cebe686

Meijling, Jesper and Tigran Haas, editors. Essays on Jane Jacobs. Bokforlaget Stolpe AB, 2020. Print.

Mehaffy, Michael W. “What was Jacobs Thinking?” Essays on Jane Jacobs. Bokforlaget Stolpe AB, 2020.

Winner, Langdon. “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” Daedalus, vol. 109, no. 1, The MIT Press, 1980, pp. 121–36, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20024652.

[1] Meijling, Jesper and Tigran Haas, editors. “Introduction,” Essays on Jane Jacobs. Bokforlaget Stolpe AB, 2020. Print.