Founder of Bethune-Cookman University and recipient of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s highest honor for promoting education for African Americans, Mary McLeod Bethune is a well-recognized figure in the field of education.[1] She believed that individuals must act responsibly and pursue education with the intent of using what they learned to serve society, a philosophy she called socially responsible individualism. Following this dedication to not only learning but also service, Bethune should be considered as both an educator and a social activist. She cultivated her idea of socially responsible individualism in Black women, believing they could improve society by achieving racial and gender equality. Specifically, Bethune provided Black women with opportunities to assume leadership positions and pursue holistic education that addressed the “head, hand, and heart.” This approach extended beyond theoretical, scholarly education as it aimed to equip women not only with foundational knowledge but also with requisite “tools” to initiate social change. Bethune’s childhood and religious background help to understand how she developed her idea of socially responsible individualism that led her to serve society as both an educator and a social activist.

Bethune’s childhood experiences provide insight into how her idea of socially responsible individualism developed and led to her life at the intersection of education and social impact. Bethune’s interest in pursuing education to help others began at an early age. Born on July 10, 1875, in a cabin in Mayesville, South Carolina, she was the first freeborn child in a family of seventeen children. Despite coming from an illiterate and poor Black family, Bethune dedicated herself to obtaining an education, walking ten miles each day to attend a local school.[2] This dedication stemmed from a childhood encounter in which she picked up and attempted to read a book but was told by a white child to put the book down as she could not possibly read as a Black person. It was through this experience that Bethune realized the importance of education and its connection to social inequality. She highlights this perspective of education when writing about why she became an educator: “Mr. Lincoln had told our race we were free…mentally we [African Americans] were still enslaved.”[3] With this motivation, Bethune learned to read. However, she did not learn to read solely for herself. In fact, as soon as she acquired literacy skills, she read Biblical stories to her family members. Demonstrating how she not only cherished her own education but also believed in using it to benefit others, this perhaps marks the beginning of her life dedicated to socially responsible individualism.

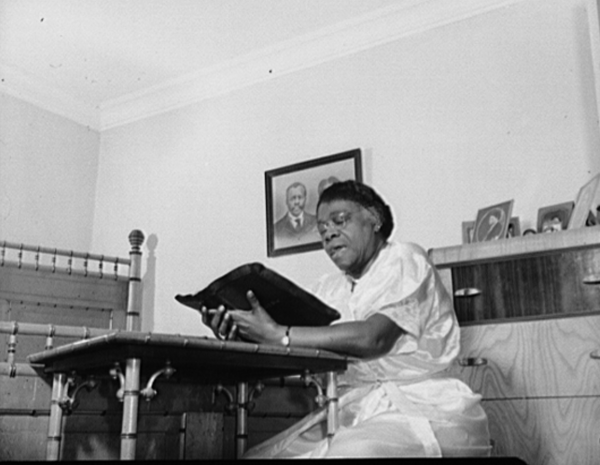

Bethune read from her Bible each night (1943). Her deep connection with religion inspired and motivated her dedication to socially responsible individualism.

Source: https://www.loc.gov/item/2017843213/

Bethune’s personal connection with religion encouraged her to serve others and guided her to connect education with service as a socially responsible individual. Writing in her 1946 essay “Spiritual Autobiographies,” Bethune reveals how her religious background was a driving force behind her educational work aimed at improving the social conditions of African Americans. She states that her belief in God guided her and led her to use love and forgiveness as her “weapons” in the fight to achieve equality.[4] This compassionate approach led her to trust many people, which later helped advance her work because she believed in and supported individual and collective action. Moreover, Bethune notes that the Biblical passage John 3:16, “whosoever believeth in Him should not perish,” sparked her interest in using education grounded in religious ideals to benefit society, which led her to prepare for missionary work. This religious background helped solidify her overall goal to use education to create positive social impact and shows how Bethune herself led a life as a socially responsible individual.

Building on these formative educational and religious experiences, Bethune demonstrated her dedication to socially responsible individualism through her active pursuits combining education with social impact. As a young adult, Bethune embodied her idea of socially responsible individualism as she pursued education with the intent of serving others. Hoping to become a missionary in Africa so she could educate and improve the social condition of Black people, she studied at Scotia Seminary in North Carolina. After graduating in 1893, she continued her preparatory missionary studies at the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. She later applied to be a missionary but was rejected as she was considered “not well suited” for missionary work as a Black woman. Initially, this led her to see herself as a failure in terms of her idea of socially responsible individualism because she could not employ her education to benefit others. However, she soon realized that she could fulfill her goal of educating and improving the lives of Black people directly in the United States. After this realization, she journeyed to Haines Industrial in Georgia, working with Lucy Laney who pioneered promoting education of Black children. Inspired by Laney, Bethune moved to Daytona Beach, Florida and founded a school for Black children with the belief that education could and should be used to improve society.[5] Although started in 1904 with only a $1.50 and five students with a focus on the education of Black girls, this school, now called Bethune-Cookman University, is a co-educational institution with a $50 million endowment and 3,000 students. Its motto, “Enter to learn. Depart to Serve,” encompasses Bethune’s idea of socially responsible individualism.[6]

Bethune with girls from her school one year after its founding (1905). She is often noted for her work in education.

Source: https://www.loc.gov/item/2021669923/

Bethune provided educational opportunities to Black women to actively implement her idea of socially responsible individualism. At her school, she focused on educating Black girls as they were minorities in terms of race and gender. She specifically hoped to cultivate leaders who could achieve a more equitable society by breaking down racial and gender barriers. In her 1926 essay “A Philosophy of Education for [Black] Girls,” Bethune outlines her belief in how education of Black women could achieve a more equitable society. She writes that women need a “certain type of intellectual training” to enable them to “contribute to the growth and development of the race.”[7] Although this intellectual training would teach about the responsibility women have at home, it would, more importantly, demonstrate that they were to use their education and inherent “creativity to remove walls of race.”[8] This helps to show that Bethune saw education as a “toolbox” that a woman needs for when “she leaves the school life and enters Life’s school.” [9] Drawing on practical principles from math, history, and economics, Bethune helped women create this toolbox to prepare them to fight gender norms and cultivate a harmonious, equitable atmosphere both at home and more broadly in society. Bethune herself challenged traditional barriers as she remained steadfast in her working role although her husband saw himself as the “male breadwinner” after the birth of their son.[10] Although this educational approach aimed to enact change at the individual level, specifically in households of Black women, Bethune also sought to initiate social change through collective social action.

In addition to serving as an educator, Bethune worked as a social activist by creating and promoting social organizations that focused on expanding her idea of socially responsible individualism. While more informal than direct schooling aimed at individuals, these organizations sought to provide Black women with the skills and places needed to take initiative and become leaders in society. She believed Black women could assume leadership positions through which they could make evident and address the inequality faced by women and African Americans. This most notably came to fruition through the National Council of [African American] Women (NCNW) of which Bethune served as president until 1949.[11] The NCNW followed Bethune’s idea of socially responsible individualism as it helped women extend what they learned into the social realm by providing them with leadership and collaboration opportunities through which they could advocate for equality. Through these collective actions grounded in educational and leadership opportunities, Bethune believed that Black women could achieve equality and, in turn, improve society.

Bethune with Eleanor Roosevelt at a National Youth Administration (NYA) meeting (1935-1942). Bethune was head of the African American Division of the NYA under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Source: https://www.loc.gov/item/2017767762/

Moreover, Bethune’s active engagement in politics highlights how she bridged education and social activism and led a life as a socially responsible individual. Although she primarily focused on providing opportunities to Black women, Bethune strongly believed she could help African Americans more generally by advocating for education of Black children and civil rights. Exemplifying her idea of socially responsible individualism, she took the initiative to assume positions in government organizations regarding education and social activism. Under President Hoover, she served on the 1930 White House Conference on Child Health and Protection which aimed to promote awareness about issues affecting children.[12] Under President Franklin D. Roosevelt and in collaboration with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in 1934, as the head of the [African American] Division of the National Youth Administration, she supervised educational training of 600,000 Black children. Additionally, in 1945, she served on President Truman’s Civil Rights Commission to investigate and protect civil rights.[13] These experiences help to show how she advocated for the rights of African Americans from a broader, political perspective that connected her educational background with social impact.

Additionally, Bethune’s writings help to show how her contribution to society involves both education and activism. Like other Black intellectuals in the 20th century, Bethune focused on racial inequality and actively wrote for African American newspapers, such as The Chicago Defender. In addition, she published essays and was in conversation with prominent government leaders and Black intellectuals. Although she shared views and drew inspiration from noteworthy individuals, including W.E.B. Du Bois, her work was unique because of her action-based idea of socially responsible individualism bridging education and social activism.

A summative example of how Bethune’s life and her idea of socially responsible individualism involved both education and social activism is her 1944 essay “Certain Inalienable Rights.”[14] From an essay collection centered around ending segregation through a “new system of equality,” this essay helped lay the “path that the civil rights movement…would follow.”[15] Tracing back to the origins of American democracy, her essay parallels the Declaration of Independence, using “inalienable” instead of “unalienable,” and actively calls for social change by developing a sense of immediacy and urgency. Bethune emphasizes how her idea of socially responsible individualism is not only about education as she connects it with a broader social and political standpoint focused on American democracy. Stating that an African American “wants only what all other Americans want” but without this America “will be that much less a democracy,” she outlines a “program for racial advancement and national unity.”[16] Her plan required education, such as through special programs, so that individuals would be equipped to fight inequality and ultimately improve society. This plan also focused on collective action through federal and public cooperation to provide African Americans with educational opportunities. She believed this foundational education would enable African Americans to understand and utilize their right to vote, ability to work, and capacity to serve in the armed forces. This would secure the rights of African Americans and empower them to fight inequality to help achieve democracy. As stated in the description about her political work, Bethune collaborated with government and social organizations to bring her written word into action.

Mary McLeod Bethune died on May 18, 1955, but her legacy lives on through her impact on education and society. She is remembered at Bethune-Cookman University, where she is buried; her house, a National Historic Site; and, most recently, with a statue soon to be displayed in Statuary Hall in Washington, DC.[17][18] Her guiding principle of socially responsible individualism shows how her childhood and religious background influenced her to use education to serve others. Bethune’s involvement in educational, social, and political organizations helps to show her importance not only as an educator but also as a social figure. The ways in which she brought her written word into action highlight how she aimed to empower Black women to become socially responsible individuals in a way that would facilitate social advancement of African Americans more generally. As both a woman and an African American involved in education and social activism, Bethune provides a unique perspective on life during the 19th and 20th centuries and highlights the positive outcomes of a life dedicated to socially responsible individualism and her school’s motto of “Enter to learn. Depart to serve.”

About the Author

Bernadette Miao is an undergraduate majoring in Chemistry and Biological Chemistry. She enjoyed learning about Mary McLeod Bethune, specifically how Bethune dedicated her life to promoting education aimed at improving society. As she aspires to develop medical therapeutics and help people through a career in science and medicine, she admires Bethune’s dedication to serving humanity through her involvement in education and social activism.

References

[1] Joyce A. Hanson, Mary McLeod Bethune and Black Women’s Political Activism, University of Missouri Press, 2003, Chapter 1.

[2] Gerda Lerner, ed., Black Women in White America: A Documentary History, Pantheon Books, New York, 1972.

[3] Gerda Lerner, ed., Black Women in White America: A Documentary History, Pantheon Books, New York, 1972.

[4] Audrey T. McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1999.

[5] Joyce A. Hanson, Mary McLeod Bethune and Black Women’s Political Activism, University of Missouri Press, 2003, Chapter 1.

[6] Joyce A. Hanson, Mary McLeod Bethune and Black Women’s Political Activism, University of Missouri Press, 2003, Chapter 2.

[7] Audrey T. McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1999.

[8] Audrey T. McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1999.

[9] Audrey T. McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1999.

[10] Joyce A. Hanson, Mary McLeod Bethune and Black Women’s Political Activism, University of Missouri Press, 2003, Chapter 2.

[11] Elaine M. Smith, Mary McLeod Bethune and the National Council of Negro Women: Pursuing a True and Unfettered Democracy, Alabama State University, 2003.

[12] U.S.C.S.C. on Rules and Administration, Memorial to Mary McLeod Bethune, Washington, DC, 1960.

[13] Gerda Lerner, ed., Black Women in White America: A Documentary History, Pantheon Books, New York, 1972.

[14] Rayford W. Logan, What the Negro Wants, Agathon Press, New York, 1969.

[15] Audrey T. McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1999.

[16] Audrey T. McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1999.

[17] U.S.C.H.C. on Interior and Insular Affairs, Authorizing the National Park Service to Acquire and Manage the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site, Washington, DC, 1991.

[18] Rachel Treisman, This Statue of Mary McLeod Bethune Will Soon Make History at the U.S. Capitol, NPR, 2021.