Ban Zhao (48–117 CE) was born into a wealthy and educated family. Her background allowed her to create literature about female conduct that would please men in a position of power. Her credibility was made possible by the Ban family’s ties to the imperial authorities, and the family’s accomplishments including extraordinary scholarly and literary achievements. Growing up in such an educated, talented family, Ban was immersed in the learning of influential Chinese philosophy and literature. Rare and valuable books, copies of inaccessible palace manuscripts, were all supplied to Ban, uncommon for women of her time. Furthermore, she was exposed to the diverse philosophical schools prominent in her time, and the impact of Confucianism and Daoism was reflected in her writings. Unlike other women, Ban’s marriage also allowed her to dedicate herself to academia. Ban Zhao married at age 14, but her husband died while she was still young. She never remarried and was allowed to focus on studying literature. Her unique educational background and status as a widow allowed her to organize some of the most influential pieces for woman’s gender in Chinese history. Many of Ban Zhao’s ideologies may seem backward and unreasonable in the modern context. However, her work was extremely influential in the past and still impacts modern Chinese society. In addition, it may also be argued that her work still has practical applications.

Ban Zhao’s most influential piece of philosophy is Percepts for Women. Ban Zhao composed this piece when she was more than fifty- four years old. This period is also the zenith of her career. Her motive for drafting the piece is unclear but most historical scholars suspected that her motive was to give guidance to girls who were about to be married. The piece serves as guidance on how they can behave when they go into their husband’s families. Because of this work, Ban Zhao holds a unique place in the history of Chinese philosophy and is recognized as the first thinker ever to formulate a single complete compilation of feminine ethics[1]. The work contains an explanation of the science behind perfecting the womanly character, a system of theoretical moral disciplines, and also rules for practical application of these principles. This work is separated into seven different chapters, and this blog will separate the Percepts for Women into two sections- “control over ideology” and “control over speech, behavior, and marriage.”

For many, Ban Zhao’s Percepts for Women stand out as the antithesis of modern feminism. Indeed, scholars criticized Ban for her discriminatory ideas. However, even in modern times, many scholars recognized her significance and praised her intelligence. Nowadays, Chinese’s special emphasis on family and lasting discouragement of certain feminist ideals can still be explained by the influence of Ban’s work. In 1932, Nancy Lee Swann recognized Ban Zhao as the first thinker to formulate a single complete statement of feminine ethics and re-affirmed her positive image in the history of Chinese women, rather than criticizing her.[2] Ban’s advocates argued that Ban proposed anti-feminism ideals to ensure the survival and cohesiveness of families. By advising women to inferiority, Ban was trying to ensure familial wellness. Familial wellness is still a highly important idea in Chinese society and the last section of the blog will highlight the practical implication of Ban’s emphasis on families while discussing its ties with modern sociology studies on families[3] and Gary Becker’s strain of economics.

Control Over Ideology

Percepts for Women attempts to offer a series of rules that restrains women to an inferior position in society. In Ban Zhao’s work, the first chapter is titled “Lowly and weak.”[4] This is her definition of the position of women in traditional Chinese society. She wrote that women must “endure insults and swallow smears, and constantly live as in fear” and she needs to live in “purity and quietness.”[5] This beginning chapter sets the tone for the overall piece and evidently conveys the inferior position of women. Then, Ban proceeds by discussing that a husband should control his wife and husband need to establish rules of conduct to manifest his authority. Ban supports this argument by utilizing the Yin and Yang principles from the Confucian classic Yijing. In Yijing, Yang normally represents men and Yin represents women. According to Ban’s third chapter “Yang’s quality is hard and Yin’s application is soft; men are valued for their strength while women are praised for their weakness.”[6] According to the system of Yin and Yang, women should not be capable and powerful. Instead, they should practice weakness and be governed by men. This system of ideology from Ban defines her definition of a gentlewomen’s proper mentality and beliefs. However, she is largely criticized for those ideologies in modern times.

Instructions for Chinese Women & Girls by Ban Zhao. Source: Amazon.com

Ironically, Ban did not exemplify the characteristics, nor did she try to uphold her ideologies herself. In Ban’s time, Dowager Empress Deng was the actual ruler of the country. She was given this opportunity because when her husband faced an unexpected death, the elder son of the family was not yet named emperor. Instead of behaving like a weak and lowly woman, Empress Deng nominated a sickly infant to be the king so that she can rule. Ministers who spoke against her were largely eliminated to solidify her power.[7] The Dowager Empress was Ban Zhao’s pupil and she made Ban Zhao her most trusted adviser. However, Ban Zhao herself never spoke against the Dowager Empress’ ambition as an emperor. She did not uphold the standards that she has set for others but rather followed an opposite path. As Empress Deng’s advisor, Ban was exalted to a height in the history of China that is unmatchable by most women. She received an excellent education in literature, scholarship, and politics. Yet, in the second chapter, Ban still recommends women receive only elementary education from eight to fifteen. In chapter 4, she set rules to deem women’s characteristics:

“Speaking of a woman’s virtue, it is not necessary for her to be brilliant, outstanding, or unique. As to a woman’s speech, she need not be gifted at debate or be skilled with words. A woman’s appearance needs not to be beautiful, and a woman’s work need not be cleverer than others.”[8]

For many, Ban’s work contradicts herself and many argue that she was never in the position to write Percepts for Women. She herself never exemplified herself as a weak woman, and clearly don’t follow her own writings. However, she still advises women to mediocracy. The exact reason for this is unclear in the midst of history. But, an explanation for this might be Ban’s attempt to ensure familial cohesiveness. In some accounts of history, Ban lamented over the loss of her husband and experienced significant difficulties when raising her children. She also experienced torturing loneliness in her old age and started to lone for true marriage. To some extent, Ban wanted a well-cohesive family. Therefore, when her grandchildren are ready for marriage, she truly hoped all of them can get a loving family. The Percepts for Women advises the women to an inferior position to ensure they can please their husbands. The reason that Ban believes in feminine weakness instead of male weakness is because of Yijing. Adhering to Daoist and Confucianist Yin and Yang principles that designate women to a weaker position, she might be trying to guide all future women to a “right” route.

Control over Speech, Behavior, and Marriage

Ban also sets dehumanizing rules for women’s appropriate speech, behavior, and conduct in marriage. Specifically, she is a strong advocate of soft speeches and action for women. In chapter 4, Ban stated that women should, “choose [their] words carefully, and utter not vile words. Speak only at the appropriate moment. Avoid offending others.”[9] In this account, women are discouraged from being argumentative and expressing their thoughts.

Furthermore, Ban’s most argumentative piece of control over behaviors restricts women to a place without any happiness. She clearly said that women should be quiet and pure, and focus on family work instead of “jesting and laughing.” Also, women “should not listen to gossip in the street,” “dart sideways glances,” “put on seductive appearance,” “gather together with their friends, or peep out of doors and windows.”[10]

Those are harsh regulations on the behaviors of women. If they were to be followed word by word, it is likely that women would have had to forgo all of their happiness and interests. They would also never enjoy neither relaxation nor entertainment of any kind. If women aren’t allowed to gather and have friends and are only subordinated to follow their husbands, they are becoming prisoners with a life sentence.

However, those properties of women make sense for Ban, because they are necessary to keep a healthy familial relationship and contribute to the general health of society. In chapter 3, Ban argues that if the husband and wife are intimate enough, they will undoubtedly have arguments. During those arguments, the husband will become angry and potentially beat his wife.[11] Therefore, it is important for women to keep themselves in their proper place and not speak openly against their husbands. Furthermore, in chapter 6, Ban argues that women are instructed to obey the mother-in-law regardless of whether the latter is right or wrong. [12

Ban insists on those laws because she presupposes the importance of familial cohesiveness and the natural weaknesses of women. In Ban Zhao’s ideology, a man can remarry while a woman may never do so. In chapter 5 of Percepts for Women, she gives the following reason:

“According to the books on propriety, there is justification for men to remarry, but there is no text upon which the remarriage of women can be based. Hence we say, the husband is like heaven; there is no way we can escape from heaven, similarly, women cannot leave their husbands.”[13]

Ban’s strict restrictions on women’s positions are largely criticized by many scholars. According to studies by Liu Dehan, women in Eastern Zhou Dynasty tends to remarry.[14] Remarriage of women is not uncommon prior to the Han Dynasty that Ban resides in. In fact, there is also evidence that it was customary for women to remarry if their spouses had died or if they had been divorced. There are also extreme cases in which the wife’s family initiates a divorce. Therefore, Ban’s standards seem extremely contingent for her period. The possible reason for Ban’s extreme position lies in her educations in Daoism and Confucianism. Her ideals followed many rules generated from Confucianism and Daoism. She was suspected to propose those extreme arguments as a measure to revive some Confucianism and Daoism principles.

Conclusion and Practical Application

In Ban’s philosophy, she puts women in an inferior position and advises them to mediocracy. Justifying her ideals with Yin and Yang, Ban formulated a series of restrictions on feminine ethics. She thinks women need to stay pure, quiet, and obedient. Also, they should restrain their behaviors, such as not listening to street gossips or putting on seductive appearances. She proposes those restrictions to ensure family cohesiveness and it is important to note that Ban does not completely neglect the power of women completely. Instead, she actually considers the women to be closely related to family honors. In fact, Ban presents women with familial agency. Familial agency, which is based on submission and obedience to its members, demands women to seek acceptance, status, honor, and respect from their husbands and the greater community[15]. Ban pushed women to adhere to traditional female ideals like humility, domesticity, reliance, submissiveness, and obedience. Such Chinese women’s agency could only be expressed through supporting the family’s well-being, and women’s ambition and power were exercised in and through the family. Even in the modern world, Ban’s work and the idea of familial agency still have a profound impact on Chinese society.

Although almost no serious attention was given to Ban’s Percepts for Women right after Ban’s death, her work was revisited in the Ming Dynasty and received unmatched attention during Neo-Confucianism. Emperor Shen of the Ming Dynasty grew profound interest in Ban’s work and named it the lead of the four books to be studied by women. From that point onwards, every literate woman began her career by reading the Four Books for Women. This situation continued until modern Chinese education was largely impacted by the western transplanted feminist ideals. But, even today, many Chinese are still reluctant to accept feminist ideologies and many women still prioritize their work in the “domestic sphere.” This has led many to suspect that there are still practical applications of Ban’s work.

Setting aside the dehumanizing antifeminism ideals, Ban Zhao’s emphasis on familial agency and family cohesiveness can have practical applications in the modern world. Although the sole emphasis on females’ sacrifice may seem brutal and unreasonable, the theories’ ultimate significance given to the importance of a cohesive family is important in the modern context.

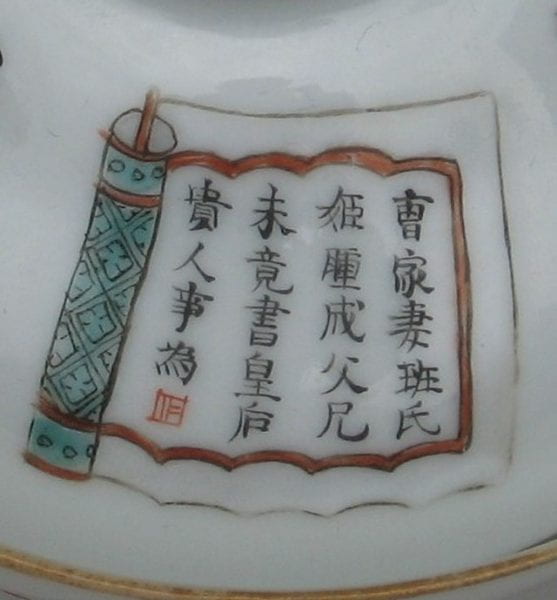

Ban Zhao’s Poem. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

According to sociology studies on the well-being of future generations, a cohesive family seems to be a vital factor. Children from single-parent and stepparent families evidently have higher poverty rates. They also experience lower levels of educational and occupational attainment than children who grow up with both their biological or adoptive parents.[16] Families’ income, care, and attention to children are all aspects of influence. Ban’s advocation for less familial arguments is also important. Parental conflict is associated with children’s negative schooling outcomes, behavior problems, early and nonmarital family formation, lower quality adult relationships, and lower psychological well-being. If familial agency is emphasized, children’s development and future generations will be significantly benefited. Sacrifices, either by woman or man, in a family, will be important for the development of future generations.

Besides, Gary Becker’s theories on family economics also support Ban’s proposed familial agency of women. For Gary Becker, people marry for the same reason that nation trade with each other. If men excel in the labor market, while women are better at raising children, it makes sense for them to specialize in their field.[17] Combined with Ban’s theory, it is natural that women excel when they are expressed in the familial agency. Therefore, women should specialize in their skills to maximize utility. If men can specialize outside, and women can specialize in their in-family tasks, they will have a close-knit marriage that will provide marital-specific capital. This marital-specific capital is beneficial for the family and can enable better development.

Although Ban’s restrictions on women’s ideologies and behaviors are not applicable in the modern world, her emphasis on feminine development in families and family cohesiveness still has practical implications. Family cohesiveness will benefit future generations, and specialization in families will be more beneficial for both males and females. Those practical implications explain how Percepts for Women still have a lasting impact in the modern world. It provides reasons for why many Chinese are still not pro-feminism and why staying in the domestic sphere is still a popular choice for Chinese females.

References:

Featured Image: Ban Zhao. Source: The Vintage News 2016.

[1] Lee Lily Xiao Hong, The Virtue of Yin: Essays on Chinese Women (Broadway, NSW: Wild Peony, 1994), 15.

[2] Nancy Lee Swann, Pan Chao: Foremost Woman Scholar of China (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese studies, University of Michigan, 2001).

[3] Kelly Musick and Ann Meier, “Are Both Parents Always Better than One? Parental Conflict and Young Adult Well-Being.” Social Science Research 39, no. 5 (2010): 814–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.03.002.

[4] Ban Zhao, Nvjie, Chapter 1

[5] Ban, Nvjie, Chapter 1

[6] Ban, Nvjie, Chapter 3

[7] Hong, The Virtue of Yin: Essays on Chinese Women, 9

[8] Ban, Nvjie, Chapter 4

[9] Ban, Nvjie, Chapter 4

[10] Ban, Nvjie, Chapter 2-4

[11] Ban, Nvjie, Chapter 3

[12] Ban, Nvjie, Chapter 6

[13] Ban, Nvjie, Chapter 5

[14] Deshan Liu, Dong Zhou Fu Nv Sheng Huo, 63

[15] Lin-Lee Lee, “Inventing Familial Agency from Powerlessness: Ban Zhao’s lessons for Women.” Western Journal of Communication 73, no. 1 (2009): 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570310802636318.

[16] Musick, “Are Both Parents Always Better than One? Parental Conflict and Young Adult Well-Being”

[17] Robert Pollak, “Gary Becker’s Contributions to Family and Household Economics,” 2002, https://doi.org/10.3386/w9232.