“I was in lots of raids before. All the street queens were. The paddy wagon was a regular routine. We used to sit in our little 42nd Street hotel rooms — ‘hot spring hotels,’ they used to call them — and party and get high and think about walking down the street someday and not worry about getting busted by the police. That was a dream we all had, sitting in those hotel rooms or in the queens’ tanks of the jails. So, honey, when it came that night, I was ready to tip a few cars for a dream. It was that year — 1969 — when I finally went out in the street in drag full-time. I just said, ‘I don’t give a shit,’ and I’ve been in drag most of the time since.”

When looking upon the history of social sciences, a group that is often overlooked is the challengers of the status quo, the activists working tirelessly on the streets to initiate tangible change in our society. In the mid to late twentieth century, we saw an uprising in social riots, one of these specifically working toward more rights for the LGBTQIA+ community. At the forefront of this movement was Marsha P. Johnson, the P standing for “Pay it no mind”.

Born on August 24th, 1945, Marsha worked to be at the forefront of gay liberation and activism, explicitly working behind the movement of uplifting “transvestites”. Defined as “homosexual men and women who dress in clothes of the opposite sex”, Marsha was a fierce believer in providing freedom to those traditionally ridiculed by society at this time. The work of her and other trans activists would create a queer community to be modeled off decades later and even today, can we see her works being acknowledged.

Mural of Marsha P. Johnson, 2020. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Leaving home at the age of 18, Marsha began to live her life as a trans woman after being ridiculed many times for the way she dressed and traumatic sexual experiences.

“As I was growing up, I met a lot of men. They never appealed to me, you know, too much sexually. You know, I tried to keep away from them because in my hometown if you were homosexual you were out of it and they would call you all kinds of names. And then when I first came to New York, I was 17 years old that’s when I started getting kind of— you know— transvestite, more like a transvestite. I started out with makeup in 1963-1964 and in 1965 I was coming out more and I was still wearing makeup. But I was still going to jail just for wearing makeup. In 1969, I started wearing female attire full time.”

Operating as a drag queen in the New York neighborhood she now lived in, her attire didn’t stray too far from the regular red plastic heels, a hair bouquet sourced from her times of homelessness, and various grand wigs that would draw the attention of any crowd. I would say that Marsha’s defiant nature against the unfavorable reactions to transvestites and drag queens during this time period provided a strong foundation for gay pride to come many years after. Also, we see through her experiences the development of what it means to be trans in society. At the time, Marsha saw herself as someone who identified differently as the sex they were born with, which was male in Marsha’s case.

One could argue that we can see the development of gender non-conforming and non-binary identities here since Marsha existed within this intersection of being both a homosexual man and a trans woman/drag queen. Here I refer to what many would call Marsha’s alter ego or “male persona”, Malcolm (her assigned-at-birth name). Described as a more violent and rash personality, Marsha’s entire presentation would change and impersonate a more masculine, forceful ideal. It would lead her to many run-ins with the police and many times lead to hospitalization due to this deterioration in her mental health.

“This last breakdown, I was fighting with everyone. I don’t like getting in those fights, but when they say you can’t stay and you don’t know why… When I’m having a breakdown it seems like I meet all these weird people, all these strangers who don’t understand gay people coming around. I know something is coming on and I light my candles and incense and pray to my saints. Sometimes I have visions. In one of them, there were 10 suns shining in the sky, gorgeous and freaked out, like the end of the world. I love my saints, darling, but sometimes the visions can be scary.”

Her rise to becoming a vanguard of the gay liberation movement began with the 1969 riots at the Stonewall Inn. Many people credit Marsha with throwing the first punch, though she has denied this claim many times. This doesn’t mean she wasn’t one of the riots’ most prominent figures. She worked with many other activists during the uprising, pushing against the various police attacks occurring at the time. This rebellion gave energy to a more forceful push towards the access of LGBTQIA+ rights and set the stage for future congregations, including the first gay pride parade. I like to describe it as a gay “renaissance” in that activism and study of transgender theory skyrocketed.

The following year, we see the creation of one of Marsha’s most powerful works and legacies. Marsha had led the organization of a sit-in at Weinstein Hall at New York University with members of the Gay Liberation Front and Radicalesbians in response to an organization canceling an event after finding out its sponsorship from gay organizations. What resulted from this direct action was the creation of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) and the STAR House. Sylvia Rivera, Marsha’s fellow revolutionary, described it as a place “for the street gay people, the street homeless people, and anybody that needed help at that time. Marsha and I had always sneaked people into our hotel rooms. And you can sneak 50 people into two hotel rooms.” Organizing shelter for trans and gay youth was something of importance to Marsha since homelessness was a returning aspect of her life. The STAR House was funded through sex work that Marsha and others would complete at the time, preventing the youth staying within the shelter from having to do it themselves.

Marsha, along with others within the STAR House, drafted its manifesto, which provided their social and political ideology. Describing its writers as revolutionaries, the manifesto offered a very socialist and communal ideal that would later inspire the formatting of the gay liberation movement. Here I will go through each of its bullet points.

1) “We want the right to self-determination over the use of our bodies; the right to be gay, anytime, anyplace; the right to free physiological change and modification of sex on demand; the right to free dress and adornment.”

Here we see the fight for fundamental freedoms within gay liberation, such as transvestites wanting to be able to exist in a space without judgment. We also see gender-nonconforming undertones with the want of being able to transition between various gender identities.

2) “The end to all job discrimination against transvestites of both sexes and gay street people because of attire.”

This is pointing toward the end of any bigotry that many trans individuals at the time faced. The clothing that they wore led to lots of harassment and hate from various groups of people. The hope was that they could live freely if they weren’t constantly targeted by the intolerant public.

3) “The immediate end of all police harassment and arrest of transvestites and gay street people, and the release of transvestites and gay street people from all prisons and all other political prisoners.”

Johnson and many of her friends were constantly sent to jail because of the previously mentioned intolerant public. Being trans in society was seen as a threat, something that had to be locked up and sent away. As we know, police harassment has always been an issue with regard to various marginalized groups in society, and here the STAR members are calling for an end to this. We even see them call for the release from political prison, which can point to the very hostile political environment that existed at the time.

4) “The end to all exploitive practices of doctors and psychiatrists who work in the field of transvestism.”

Trans individuals have constantly been mistreated by healthcare providers, and at many times, have been taken advantage of. The medical field can be very discriminatory towards the lives of trans people, and it’s an issue we even face in today’s society. Here we see the call to end this mistreatment.

5) “Transvestites who live as members of the opposite gender should be able to obtain identification of the opposite gender.”

This kind of ties into the earlier bit where it is mentioned that the political climate at the time was very hostile towards trans individuals. Not being given the option to live their lives as their true gender can lead to harmful and life-threatening situations. The government allowing trans individuals to obtain the correct type of identification is crucial.

6) “Transvestites and gay street people and all oppressed people should have free education, health care, clothing, food, transportation, and housing.”

This is where we see lots of socialistic practices come into play. The idea of being provided with the basic necessities of life without any further cost is demanded. We also can see a more gender-nonconforming approach to this, with the mention of all oppressed people. This is an issue that not only plagues trans people but literally anyone of any identity who the government has discriminated against. This socialist idea helps form the basis for the future of the LGBTQIA+ rights movement since it is all about helping and providing for each other.

7) “Transvestites and gay street people should be granted full and equal rights on all levels of society, and full voice in the struggle for liberation of all oppressed people.”

We once again see more socialist ideas here. Johnson and others wanted their community to be seen as equals and not as low-tier members of society. They wanted to be heard, and they especially wanted the voices of trans individuals to be heard when it came to the general social rights movement.

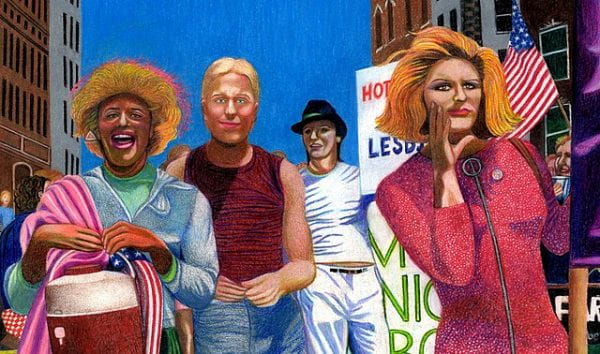

Portrait of Marsha P. Johnson, Joseph Ratanski and Sylvia Rivera in the 1973 NYC Gay Pride Parade by Gary LeGault. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

8) “An end to exploitation and discrimination against transvestites within the homosexual world.”

Johnson had frustration with the politics of the gay liberation movement at the time. STAR was formed as a pushback against the movement being dominated by more masculine gay men who felt threatened by trans individuals. We can see even today hostility towards trans individuals within the community, and some aim to continue to exclude them. It’s hard to work towards bringing awareness to a specific problem when the people who are supposed to be of direct support are actively trying to exclude you.

9) “We want a revolutionary peoples’ government, where transvestites, street people, women, homosexuals, puerto ricans, indians, and all oppressed people are free, and not fucked over by this government who treat us like the scum of the earth and kills us off like flies, one by one, and throws us into jail to rot. This government who spends millions of dollars to go to the moon, and lets the poor Americans starve to death.”

The manifesto ends with the return to the revolutionary ideal. Johnson and others were not only trying to fight for rights for trans individuals but also the entire section of society that consisted of minority groups and oppressed people. Society and our government did little to nothing for support, and instead imprisoned a lot of these people. This was at the time where we were sending only privileged white men to go walk on the moon. As someone who is interested in pursuing a career in the space industry, I think this frustration is absolutely justified. Members of minority groups were being discriminated against, dying, and being provided little support. It only made sense for them to band together and produce documents similar to this manifesto, and work as a community for a better life. The government wasn’t going to help them, so who else did they have?

Exploring the history of activism in transgender theory is crucial since simply acknowledging that transgender and gender non-conforming people exist doesn’t do enough in our society and the texts we aim to create. Marsha Johnson was a crucial figure in making sure that in the gay liberation movement, trans individuals were included and represented, and made an impact on Trans and LGBTQIA+ theory for years to come. Her activism in creating a socialist community for trans individuals has and will continue to have such a profound effect on how we view transgender theory today.

About the Author:

Joalda Morancy is a 4th year majoring in Astronomy and Astrophysics. When not doing schoolwork, they enjoy consuming all forms of science fiction.

Bibliography:

Featured Image: A 1970 photo of Marsha P. Johnson handing out flyers in support of Gay Students at NYU is seen here courtesy of the New York Public Library’s “1969: The Year of Gay Liberation” exhibit.

Breaux, H. P., & Thyer, B. A. (n.d.). Transgender theory for Contemporary Social Work Practice … Retrieved from https://jswve.org/download/2021-1/2021-1-articles/72-Transgender-Theory-18-1-Spring-2021-JSWVE.pdf.

Chan, S. (2018, March 8). Marsha P. Johnson, a transgender pioneer and activist. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/obituaries/overlooked-marsha-p-johnson.html.

Feinberg, L. (n.d.). Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries. Workers World. Retrieved from https://www.workers.org/2006/us/lavender-red-73/.

Halper, A. (2019, June 25). Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera were the Mothers of the movement, but how do we tell the story of their struggles with their minds? Trans Survivors. Retrieved from https://trans-survivors.com/2019/06/25/marsha-p-and-sylvia-rivera/.

Kohler, W. (2021, June 28). #PRIDE2021 – June 28, 1969: The True Unadulterated History of the stonewall riots. Back2Stonewall. Retrieved from http://www.back2stonewall.com/2021/06/gay-history-the-stonewall-riots.html.

Pay it no mind – The Life and Times of Marsha P. Johnson. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rjN9W2KstqE.

Rubin, L. (2020, October 30). Revolutionaries on east second street: The star house. Village Preservation. Retrieved from https://www.villagepreservation.org/2020/10/29/revolutionaries-on-east-second-street-the-star-house/.

Site of the Star House (1970). Clio. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://theclio.com/entry/121132.

Sylvia Rivera Part III: Street transvestite action revolutionaries. Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries. (1970, January 1). Retrieved from https://zagria.blogspot.com/2017/09/sylvia-rivera-part-iii-street.html.

Terry, E. (n.d.). An Exclusionary Revolution: Maginalization and Representation of Trans Women in Print Media (1969-1979). Retrieved from https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013&context=honors_theses.

Watson, S. (2020, October 14). Stonewall 1979: The drag of politics. The Village Voice. Retrieved from https://www.villagevoice.com/2019/06/04/stonewall-1979-the-drag-of-politics/.

Women at the Center, says, M. F., & Frank, M. (2019, June 26). Gay Power is trans history: Street transvestite action revolutionaries. Women at the Center. Retrieved from https://womenatthecenter.nyhistory.org/gay-power-is-trans-history-street-transvestite-action-revolutionaries/.