Elinor Claire Ostrom (née Awan) was an American-based Political Scientist and Economist who was born in 1933 and passed away in 2012 at the age of 78. Today, she’s most well remembered for her contributions to the fields of New Institutional Economics and Political Economy, and as the first woman to ever receive the Nobel Memorial Prize in the Economic Sciences in 2009.

Trained as a political scientist at UCLA and tenured as a professor at Indiana University, her most well-known work, “Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions of Collective Action” developed her institutional theory by demonstrating new solutions to social issues ranging from overfishing, waterway management, and environmental stability. Her research was overwhelmingly technical, and her claims in models, game theory, and case studies not only allowed for a novel approach to these age-old problems, but in fact allowed her to contribute to world politics and give rise to an entirely new class of economists.

The origins of the future nobel-prize winner were relatively simple; She was born in Los Angeles, California, the only child of a mother and a father who were a musician and a set designer respectively. Her parents separated relatively early on in life, and growing up she attended Beverly Hills High School as she bounced between the two households.

She experienced her fair share of gender adversity when attempting to settle on a path, allegedly being “discouraged from enrolling in calculus”[1] by her high school advisor. This would actually stunt her career trajectory; Her consequential lack of mathematical skills would get her denied from multiple undergraduate and graduate economics programs. However, she rarely mentioned her struggles as a woman, even only touching on the subject when prompted at her Nobel Laureate ceremony.[2]

Elinor Ostrom (third from left) at the US Embassy in Sweden, 2009. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Nevertheless, her aspirations to contribute to social science emerged unscathed. As she earned her way through a master’s and PhD in Political Science and explored its intersection with economics, her theory of Collective Action began to take shape.

While certainly in touch with historical thought such as Malthusian population anxieties or the Darwinist “survival of the fittest” approach to Economics, Ostrom’s “Governing the Commons” is most frequently viewed as in critical conversation with an earlier work titled “The Tragedy of the Commons”. The work was authored by an American ecologist named Garrett Hardin, who reaffirmed the negative consequences of overusing a commonly shared resource, referred to as a “common”.

The Economic scenario outlined by Hardin’s writing asserts that without rules of governance, people cause a mass depletion of their common resources through their own reckless, self-interested consumption. This resource scarcity would result in adverse consequences such as famine, plague and death for its corresponding community. Conventional economics deemed that with any shared resource, this prophesied end result was an absolute certainty.[3] Economists saw this theory manifest itself in overgrazing and overfishing across the world.

The two existing solutions used to address this problems were government intervention, used to regulate who could use the resource when, or private ownership, where the where and when of resource consumption could be dictated at the owner’s discretion.

Where Ostrom earned her Nobel prize was by successfully proving that there existed a way to effectively manage these finite resources in a group setting without government or private ownership, both of which had non-negligible drawbacks for all those involved, such as risk of corruption. She dubbed this method “The Theory of Collective Action”, and in her work demonstrated how local communities could share collective resources like waterways, livestock pastures and forests using what were called collective property rights – guidelines on how to use and care for these resources established by the users themselves.

Not only would these agreements allow for the continued usage of commons and remove outside influence altogether, they would also have a positive future-facing impact for generations to come; They would optimize efforts like wildlife preservation and water management in an economically sustainable manner.

Ostrom’s research methodology in proving this claim had a unique distinction. While she draws expertly from game theories like the prisoner’s dilemma, she had the trait of implementing her findings from fieldwork into her writing to exhaustively prove that what she argued could work not only in theory, but in practice. As she puts it in her own words, she “mov[ed] back and forth from the world of theory to the world of action.”[4]

Her trademark methods first came into prominence during her time at UCLA’s graduate school, where she investigated the local community of Hawthorne. The city had been pumping much more water than it should have been, saving itself money and leaving the negative consequences to the other users of the waterway. While there were no legal consequences to this, it went against an already agreed-upon ruleset. Ostrom’s research found a way to enforce this agreement without invoking government intervention or privatizing the resource by thoroughly examining the primary motivators behind the initial overpumping and reacting accordingly.[5]

The city of Hawthorne was just one of the many case studies Ostrom conducted over the course of her studies. Another notable instance was the town of Törbel, Switzerland. Through extensive research of historical records, Ostrom was successfully able to confirm that for centuries, much of Törbel’s land had belonged collectively to the community of its users in a stable and non-exploitative manner.[6]

Personally, I believe an argument exists that Ostrom’s methodology shows shades of W.E.B. Du Bois’ work in Wilmington and Philadelphia; Both social scientists take an intensely people-oriented approach to their work, preferring to root their work in case studies over making sweeping generalizations. Du Bois used survey methods and archival data to determine exactly what led to the decisions behind the mass migration from the 7th Ward, and Ostrom placed a similar emphasis on understanding the decision-makers’ perspective in empirical terms to suggest an optimal strategy for Hawthorne’s water management.

Each of the thinkers also had the tendency to implement historical successes as a part of their argument as well: Du Bois cited the Pygmy people and other historical ethnic groups as hard evidence that ethnic Africans have historically had the capacity of upholding a certain standard of work. By giving this example of historical success, he managed to strengthen his contemporary argument by basing it in confirmed fact. Like Du Bois, Ostrom investigated other historical cases where her theory held true, including but not limited to “common lands in the Japanese villages of Hirano and Nagaike, the huerta irrigation mechanism between Valencia, Murcia and Alicante in Spain, and the zanjera irrigation community in the Philippines”.[7]

Du Bois was certainly not the only thinker that Ostrom’s work was in conversation with. As Greg Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons is the work Ostrom’s text is most commonly associated with, it’s interesting to juxtapose the differing cultural waters each author was swimming in.

Hardin, in his paper, cites thinker Thomas Malthus more than a few times. Malthus was a historical figure notorious for coming up with the idea of a “Malthusian Check” – Plummeting periodic dips in the population caused by “the introduction or failure of certain manufactures, a greater or less prevalent spirit of agricultural enterprise, years of plenty, or years of scarcity, wars and pestilence…”[8] Hardin believed that the inevitable depletion of commons without intervention would have a similar outcome.

Rather than reacting to the fear of famine and death in the Malthusian sense as Hardin seemed to have been doing, Ostrom seems to take a more level-headed standpoint. She clearly breaks down the elements of the social contracts she examined in her case studies of small communities without casting this anxious shadow of death.

While other thinkers have historically relied on explanations such as the advance of modern technology to explain why these “checks” have not occurred and resources not depleted, Ostrom takes upon a novel and seemingly simple solution – having faith in rational economic people to make the correct decisions amongst themselves. By being so in tune with the communities she studied, she believed that societal structures erected and maintained by the people were enough to prevent this depletion of common resources altogether.

Elinor Ostrom. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

It’s interesting to consider the implications of this more human-faithful approach in juxtaposition with the more cynical approach that had been traditionally taken in conventional economics.

Before Ostrom’s time, it was a common assumption that people needed to be governed, otherwise their selfish actions would inevitably lead to a fatal lack of resources. This was due to a concept called the “Free-Rider principle”. An essentially very dim view on human nature, this postulation stated that an immense burden would be placed on a common by its overuse “ by people who aren’t paying their fair share for it or aren’t paying anything at all.”[9] Free riders would not and will not continue to overexploit the resource, as it never stops being advantageous to them no matter the consequence on the resource pool or on the other people.

As this continued overuse was considered “economically rational”, the free-riders would need to be forced to comply with a set of rules by some outside source in order to halt their behavior. This kind of viewpoint reminds me of Thomas Hobbes, who claimed that humans were by nature anti-social, and would never willingly cooperate unless forced to. [10]

In his “Leviathan”, Hobbes describes a “warre of every man against every man”[11] – The idea that it only takes one group of people to act in their own self-interest to motivate every single other person to behave egotistically based on the fear of others also doing so. We see that very clearly in the free-rider concept, and Hobbes argues that in this “natural state”, “morals” do not exist.[12]

Hobbes sincerely doubted that humans could spontaneously create beneficial mutual contracts without enforcement. Therefore his solution to this chaotic, base, prisoner’s dilemma-esque state of humankind was to promote social contracts based on punishment and upheld by a central authority. We can draw parallels between this train of thought and the economic fine-based systems of governance brought about by government intervention and private ownership.

Ostrom’s view and faith in people to come to their senses to organize and agree on something mutually beneficial was a take utterly unafraid to turn prior convention on its head. Her words to me echo Jean-Jacque Rousseau’s work, which claimed that people could indeed create social contracts amongst themselves and ensure that people didn’t deviate from their agreements through self-governance, with each person being able to take on a little piece of accountability and responsibility.[13]

The set of assumptions that Ostrom operated under for her case studies were wholly novel to Ostrom’s work in the field of economics, and as such, new schools of thought and methods span out from these new axioms.

One such school of thought that was given new life in reaction to Ostrom’s trailblazing ontological take was New Institutional Economics. Originally coined as a unique field in 1975 by a man named Robert Coase, the major departure this field had from its more traditional counterpart was that while in the past economics assumed perfect rationality, New Institutional Economics assumes that they also do not have access to all information and also have the distinct ability to maintain agreements.[14]

Through this new Ostromian lens, the field examines the institutions that influence the socially and legally driven forces behind the economy, and seeks out the ones that could potentially enforce or implement the theory of collective action to tackle real issues of resource depletion.

Another field Ostrom’s work heavily influenced was the “Political Economy”, which was a fascinating intersection between political science, economics, and ecology designed to tackle issues like “citizenship and civic engagement, common-pool resource management, entrepreneurship…” among many other things. In fact, during her time at Indiana University, Ostrom, along with her husband Vincent, established the “Bloomington School on Political Economy” as a means of pursuing these societal issues.[15]

There, Ostrom was able to leverage her background in Political Science and contribute to world politics. In fact, she was responsible for multiple interventions between locally organized operations and national/regional authorities. For example, at one point she was invited to Nepal by its ambassador to the United States to assist in managing their water irrigation systems.[16]

In conclusion, Elinor Ostrom was undoubtedly a leading figure in shaping modern economic theory, alongside a champion of female success in the social sciences. Originating from humble beginnings, she was able to utilize a passionately case study-centric approach grounded in her political science background to establish a significantly novel ontological take on economics, a theory so well-spread that you don’t even know you know about it. Her work would not only result in globe-spanning social work in resource management, but also spawn new schools of thought dedicated to grappling with the social woes she spent her life examining.

About the Author:

I’m a second-year Economics major and Computer Science minor. Since coming to college, I’ve picked up Kendo, a Japanese martial art, at the club level and like to go on runs occasionally. I love movies and comic books, and hope to study abroad in my third or fourth year here.

References:

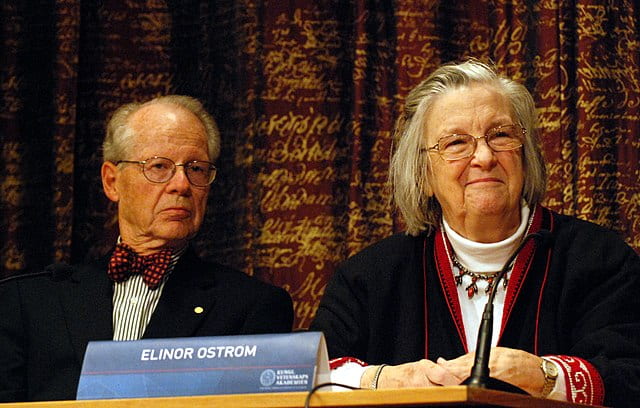

Featured Image: Elinor Ostrom in Nobel Prize press conference. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

1 May, Ann Mari, and Gale Summerfield. “Creating a Space Where Gender Matters: Elinor Ostrom (1933-2012) Talks with Ann Mari May and Gale Summerfield.” Feminist Economics 18.4 (2012): 25-37. Web.

2 Parsley, Will. “Politics Of Political Economy: Revisiting Elinor Ostrom And Garrett Hardin.” Austin, TX: University of Texas Library, 2016.

3 Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, 162, 1243-1248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

4 Ostrom, Elinor. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge [England] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990. Pg 45.

5 Parsley, Will. “Politics Of Political Economy: Revisiting Elinor Ostrom And Garrett Hardin.” Austin, TX: University of Texas Library, 2016.

6 Felice, Flavio. “Elinor Ostrom and the solution to the tragedy of the commons.” https://www.aei.org/articles/elinor-ostrom-and-the-solution-to-the-tragedy-of-the-commons/

7 Flavio, “Ostrom and the solution.” https://www.aei.org/articles/elinor-ostrom-and-the-solution-to-the-tragedy-of-the-commons/

8 Malthus, Thomas R. An Essay on the Principle of Population. London, United Kingdom, 1798. Pg 25.

9 https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/free_rider_problem.asp

10Hobbes, Thomas, 1588-1679. Leviathan. Baltimore :Penguin Books, 1968.

11 Hobbes, Leviathan.

12 Hobbes, Leviathan.

13 Rousseau, Jean-Jacques, 1712-1778. The Essential Rousseau: The Social Contract, Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, The Creed of a Savoyard Priest. New York :New American Library, 1974.

14 https://ostromworkshop.indiana.edu/library/teaching-resources/bloomington-school.html

15 Daniel Cole and Michael D. McGinnis, editors. Elinor Ostrom and the Bloomington School of Political Economy, Lanham, Maryland, Lexington Books.

16 https://newsinfo.iu.edu/web/page/normal/13009.html