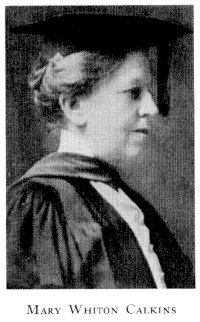

Mary Whiton Calkins, born March 30, 1863 in Hartford, Connecticut, was not only the first female president of the American Psychological Association after its foundation in 1892, but her research into dreams, memory, and self-psychology revolutionized this nascent field. Despite her illustrious publishing and teaching career, Mary Calkins was systematically denied the opportunities granted to her male colleagues, and her excellence in the field of psychology was routinely undermined by the sexist prejudices of her time (O’Connell & Russo, 1990). However, Calkins utilized her relative academic privilege to fight for the rights of women, and contributed to gender equality in academia through her own accomplishments as well as through her commitment to integrating women into social scientific research.

Mary Calkins grew up as the eldest of five children of a Presbyterian minister who avidly supported her education and encouraged her to enroll in college. After studying classics and philosophy at Smith College (1882-1885), Mary Calkins took up her first teaching position as a Greek tutor at Wellesley College in the fall of 1887 – where she would continue as a faculty member for over 40 years. After three years, her teaching excellence inspired the department of philosophy to offer her a teaching position in the new field of study within the department – psychology – which she accepted under the condition that she be allowed to study the discipline for a year (Furomoto, 1990). Due to her wish to study psychology in a laboratory setting, Calkins chose to pursue her studies at Harvard University. While President Eliot of Harvard vehemently opposed women and men studying in the same room together, he nevertheless allowed Calkins to observe lectures. Mary Calkins studied under some of the most influential researchers in the field, including William James, Josiah Royce, Edmund Sanford, and Hugo Münsterberg, who encouraged her continuing research and study of psychology, which she pursued during her long teaching career at Wellesley (Furomoto, 1990). Calkins concurrently conducted further research in the psychological field. Despite completing all requirements and the recommendations of her professors and of William James, who stated that Calkins’ was “the most brilliant examination for the Ph.D. that we have had at Harvard” (Eschner, 2017), Calkins was denied the Ph.D. she earned at Harvard due to her gender. However, Calkins expressed nothing but gratitude for the opportunity to study at Harvard, claiming that “my natural regret at the action of the Corporation has never clouded my gratitude for the incomparably greater boon which they granted me — that of working in the seminaries and the laboratory of the great Harvard teachers” (Calkins, Autobiography, 1930).

Source: https://static.hwpi.harvard.edu/files/styles/profile_full/public/psych/files/220px-mary_whiton_calkins.jpg?m=1588777939&itok=l6lXDYGg

Calkins published prolifically in both psychology and philosophy – four books and over a hundred papers – as well as compiling one of the first comprehensive psychology texts, An Introduction to Psychology, in 1901. (For a comprehensive list of published articles, refer to Mary Whiton Calkins on Google Scholar at <https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=IEWesIkAAAAJ&hl=en>.) She served as the first female president of both the American Psychological Association (1905) and the American Philosophical Association (1918), as the first female member of the British Psychological Association, and as a professor at Wellesley for over 40 years. She received honorary doctorate degrees from Columbia University and Smith College in 1909 and 1910, respectively, and was ranked by her colleagues as 12th in the list of top psychologists of her time in 1908. She founded the first female psychology laboratory in the country and is considered the first woman who earned a doctoral degree in psychology, although it was never conferred. Despite this impressive professional and academic career, Mary Calkins continues to be refused her Ph.D. from Harvard posthumously, and her contributions to the field of psychology are often attributed to the male researchers she collaborated with or are simply absent from the literature, as referenced below.

Mary Calkins’ pivotal psychological research was concentrated in three major areas, dreams, memory, and her overarching theory of self-psychology. Mary Calkins prefaced her 30-page treatise on The Self in Scientific Psychology with the statement that “the self is often bowed out of psychology on the ground that scientific introspection has failed to discover it” and subsequently questioned both the assumption that there is no evidence of the self and whether this could be attributed to its absence (and not simply to inadequate methodology) (Calkins, 1915). Here, again, Calkins pitted herself against the prominent theories of the time, which took an atomistic or idea-psychological view without reference to the self, and argued for a greater collaborative open-mindedness within the field and the importance of a double-perspective on the self. Crucially, her research focused on the assumption that the self or selves “may be treated as facts for Science,” since “they are taken for granted without inquiry about their bearing on ‘reality,’ and…. are critically observed and classified on the basis of their relation with each other and with facts of every other order,” (Calkins, Psychology as Science of Selves, 1900). Her extensive research on the self speaks to Calkins’ preoccupation with this field, and her autobiography corroborates her belief that “psychology should be conceived as the science of the self, or person, as related to its environment, physical and social. To establish this doctrine seems to me the first task of psychology and the essential preparation for its most important special undertakings,” (Calkins, Autobiography, p. 42). The scientific and biological view of the self as the foundation of the discipline of psychology (“personalistic psychology”) represented a revolutionary approach that offered a unifying system for previously divided schools of thought, including behaviorism, hormic psychology, Gestalt psychology, and psychoanalysis (Calkins, Autobiography, p. 41). Unfortunately for Calkins, her opposition to the elimination of introspection and sympathies to the social bent of the behaviorists served to make her self-psychological research unpopular to both sides of the debate between psychoanalysts and behaviorists (APA, 2011), and she spends nearly half of her autobiography attempting to answer their critiques (Calkins, Autobiography). The American Psychological Association states that, “after spending many years seeking to define the idea of the self, her work concluded that she in no way could define the idea” (APA, 2011). Self-psychology is still a fruitful area of research in the present day, and despite Calkins’ inability to come to a cohesive understanding of the self within her lifetime, her scientific and philosophical research on the subject laid the groundwork for an entire branch of the psychological discipline. Unfortunately, while her concepts achieved some initial notoriety through Gordon Allport’s 1937 publication Personality: A Psychological Interpretation, subsequent versions of the book and other research on the self have largely ignored Calkins’ work.

Under Dr. Sanford of Clark University, who also introduced her to experimental procedure in psychology, Calkins routinely woke up at different times of the night and recorded her dreams, eventually concluding that rather than a metaphysical phenomenon, dreams simply mirrored “in general the persons, places, and events of recent sense perception” and that its contents were often trivial and not necessarily “associated with that which is of paramount significance in one’s waking experience” (Calkins, Statistics of Dreams, 1893). While these findings were notably opposed to the Freudian theory of dreams, which posits that “dream-thoughts are engaged only with what seems to be important and of great interest to us” (Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, 1899) and that its manifest content disguises a psychologically revealing latent content, Calkins did acknowledge certain agreements between her research and popular psychoanalytic thought of the time. Specifically, Calkins demonstrates how she seems to have ‘predicted’ their theories that everyone dreams (with or without memory thereof) and that their content originates in the sensory experiences of waking life (Calkins, Autobiography, p. 32). Arguably, one can also identify Calkins’ early fascination with the psychology of the self in her dream research, in which she argues that “the loss of identity in dreams is not a loss but a change or a doubling of self consciousness” (Calkins, Statistics of Dreams, 1893), which was to become her main academic preoccupation.

Although Calkins favored her work on the self, her research on how frequency, recency, and vividness of exposure relates to memory retention has arguably been more pivotal to the advancement of psychological understanding. In her own words, her ‘paired-associates technique’, which paired numerals with colors as stimuli, revealed that “in direct competition, recency yields to vividness, and both vividness and recency to frequency” (Calkins, Autobiography, p. 34). This finding was not only crucial to a mechanistic understanding of human memory, but is thought to be representative of the way in which people learn in their daily lives (Deese & Hulse, The Psychology of Learning, 1967). With the rise of behaviorism, Calkins’ paired-association technique also revealed the associations between stimuli and responses, demonstrating that the pairing of stimuli utilizes two separate mental processes that learn the response and subsequently the connection between the two stimuli (Deese & Hulse, The Psychology of Learning, 1967). A brief Google Scholar search of “paired associate learning” and its 368,000 results demonstrates the importance of this discovery to the field of memory psychology, even though Calkins herself only dedicates a single page in her autobiography to the research and her original essay on associative memory has been directly cited fewer than 200 times (Calkins, Association, 1896). Sociologist Emily Cummins states unequivocally that “later, these findings would be used by psychologists who did not give Calkins credit for her work”, and Calkins herself draws attention to the adoption of her method by psychologists G. E. Müller, Titchener, and Kline (Calkins, Autobiography, p. 34). While the paired-associates technique represents a revolutionary tool in experimental psychology, its development also exemplifies Calkins’ continued philosophical consideration of the self, in which she argues that a “presupposition of the fact of association is that of the identity of the subject” (Calkins, A suggested classification of of cases of association, 1892). It is this fusion of theoretical and empirical methodologies that made Mary Calkins’ psychological research particularly productive in furthering our understanding of the human mind.

Source: https://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Calkins/calkins.jpg

Mary Calkins’ academic productivity in the face of blatant sexism is in itself a statement of resistance, yet she was also an outspoken pacifist, suffragist, and feminist. After one of her colleagues was fired from Wellesley during World War I for expressing pacifist views, Calkins tendered her resignation as a demonstration of their shared views, although this was not accepted by the institution (Foust, 2020). Perhaps most famously, Calkins rejected the Ph.D. from Radcliffe College (a women’s college associated with Harvard) that the Harvard Corporation offered her in place of the Ph.D. she had earned, arguing that an acceptance of this lesser degree – Harvard itself clarified this institutional hierarchy – would eliminate pressure on the Corporation to open the university up to women (Foust, 2020). Adopting William James’ concept of the “moral equivalent of war”, Calkins preached a uniquely pacificistic feminism of inclusivity, and utilized her academic platform to encourage the integration of women into the social sciences. Indeed, Calkins was instrumental in founding the first women’s psychological laboratory at Wellesley College in 1891, one of the first psychological laboratories in the country and the first at a liberal arts college. Originally consisting of one attic room in Wellesley’s College Hall and $200 of equipment, the laboratory eventually grew into the 14-room Wellesley College Psychology Department and hosted the 150 women students who went on to earn a doctorate in psychology at the college before 1980 (Wellesley College, n.d.).

Characteristically blunt, the APA states that “all in all, Mary Whiton Calkins was a remarkable scientist, scholar, APA President, and human being” (APA, 2011). Her dedication to her research and her self-oriented framework for the nascent field of psychology in the face of consistent gendered oppression not only makes its importance to the modern study of psychology all the more extraordinary, but paved the way for later generations of women in psychology (a field now 66.1% female (APA, 2015)). Although Calkins has undoubtedly been denied the repute owed her work, she expressed nothing but gratitude for the opportunities she was afforded, and her tenacity, ambition, and academic excellence are a testament to the crucial role of women in the foundation of the study of the social sciences.

About the Author:

Naomi Scherer is a third year double major in Psychology and Theater and Performance Studies at the University of Chicago. Next year (2022) she will be completing a Master’s degree in Social Sciences with a concentration in Psychology, studying the influence of sensory input on early cognitive development. Originally from Berlin, Germany, Naomi plans to pursue a career in medicine.

References:

Featured Image: https://feministvoices.com/profiles/mary-whiton-calkins

Calkins, Mary Whiton. “Autobiography” in History of Psychology in Autobiography. Edited by Murchison, Carl. 1930. Vol. 1, 31-61.

Calkins, Mary Whiton. “Statistics of dreams.” The American Journal of Psychology 5.3 (1893): 311-343.

Calkins, Mary Whiton. “Psychology as science of selves.” The Philosophical Review 9.5 (1900): 490-501.

Calkins, Mary Whiton. “Association (II.).” Psychological Review 3.1 (1896): 32.

Calkins, Mary Whiton. “A suggested classification of cases of association.” The Philosophical Review 1.4 (1892): 389-402.

Cummins, Emily. “Mary Whiton Calkins & Psychology: Biography & Theory.” Study.com, 2021.

Deese, James, and Hulse, Stewart H. “The Psychology of Learning.” McGraw-Hill Series in Psychology, McGraw-Hill. 3rd ed. 1967.

Eschner, Kat. “This ‘Brilliant’ Pioneering Psychologist Never Got a Ph.D….Technically.” Smithsonian Magazine, Smithsonian Institution, 30 Mar. 2017.

Foust, Mathew A. “The Feminist Pacifism of William James and Mary Whiton Calkins.” Hypatia, vol. 29, no. 4, 2014, pp. 889–905.

Freud, Sigmund, and A. J. Cronin. The interpretation of dreams. Read Books Ltd, 2013. Originally published 1899.

Furomoto, Laurel. “Mary Whiton Calkins (1863-1930).” Women in Psychology: a Bio-Bibliographic Sourcebook, edited by Agnes N. O’Connell and Nancy Felipe Russo, Greenwood Press, 1990, pp. 57–65.

“History of the Department.” Wellesley College Department of Psychology, www.wellesley.edu/psychology/history.

“Mary Whiton Calkins: 1905 APA President.” American Psychological Association, American Psychological Association, 2011.

“2005-13: Demographics of the U.S. Psychology Workforce.” American Psychological Association Center for Workforce Studies, American Psychological Association, 2015.