According to economist Christina Romer, Anna Jacobson Schwartz “wasn’t one of the best women economists. She was one of the best economists—period.”[1] Schwartz won praise and acclaim from economists for her impact on the study of economics, yet she is largely unknown outside of her field. Anna Jacobson Schwartz’s most famous contribution, A Monetary History of the United States, which she co-authored with the infamous Milton Friedman, was described by economist Michael Bordo as “one of the most important books of the twentieth century”.[2] According to Ben Bernanke, the former Chairman of the Federal Reserve, it is “the most persuasive explanation of the worst economic disaster in American history”—the Great Depression.[3]

Born in 1915, in the Bronx, New York, Anna Jacobson Schwartz entered Walton High School at the dawn of the Great Depression. While at Walton, Anna enrolled in an economics class in which the discussion

Anna Schwartz. Source: David Shankbone, via Wikimedia Commons.

centered on real-world problems, primarily the United States’ collapse into the worst economic catastrophe in its history. These class discussions inspired Anna to major in economics while attending Barnard College.[4] After graduating from Barnard at the age of 18, she was admitted to Columbia University’s Graduate Economics program. She began working on her dissertation at 21, with two other graduate students. Unfortunately, funding for her dissertation was cut because of World War II and the need to ration paper. Columbia later refused to award Anna with a Doctor of Philosophy degree, on the grounds that her dissertation was a collaborative project, instead of an independent one. Columbia’s refusal did not hold Anna back at all. Following graduate school, Anna joined the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), which was the leading economic research center at the time and continues to be such to this day.[5] At the time of her death in 2012, Anna Jacobson Schwartz had the longest NBER affiliation of any researcher—71 years.[6]While at the NBER, she began working with Milton Friedman. In 1963, they published A Monetary History of the United States, which helped found the monetarist theory of economics, impacted the way economics was taught, and influenced how research in the field was conducted, and economic policy was implemented.[7]

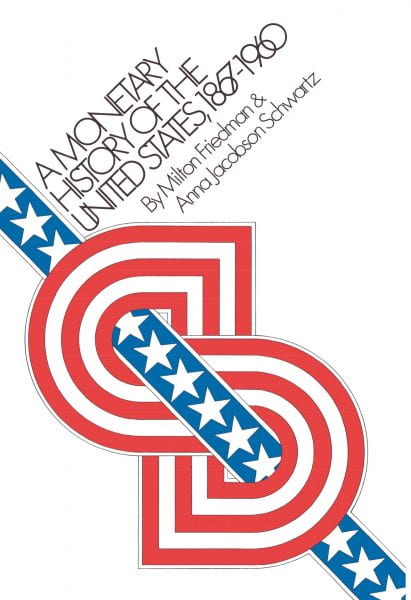

So why is it that Milton Friedman is widely known as a prominent and influential economist across many academic and public spheres, while Anna Jacobson Schwartz is awarded recognition only by those in her field? (This phenomenon, in which a woman co-author far less fandom and recognition than her male co-author for their joint work, is referred to as the Matilda Effect, a term coined by Margaret Rossiter in 1993 (the Matilda effect is the often seen as a focus on the second part of the Matthew effect when the negatively affected individual is a woman).[8] In some instances, Anna Jacobson Schwartz is not even recognized as a co-contributor, much less given proper credit for her work. The Milton Friedman section in The Encyclopedia Americana (2002 edition) states, “His major work, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, was published in 1963”.[9] Anna Jacobson Schwartz’s existence is completely ignored. Similarly, when awarding Milton Friedman with the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1976, the Nobel Committee described A Monetary History of the United States as Friedman’s “major work [and] … one of Friedman’s most profound and also most distinguished achievements”.[10] Schwartz’s contribution was not mentioned. Milton Friedman himself recognized the clear differences in the acknowledgement of their work. Emphasizing how much of a contribution Anna Jacobson Schwartz made to their joint publication, Friedman claimed “Anna did all of the work, and I got most of the recognition”. [11] Even the memorial news articles honoring her legacy after her death refer to Anna Jacobson Schwartz as Friedman’s co-author, presumably to generate greater attention to Anna than she otherwise would have earned.[12]

Cover art of the most recent volume of A Monetary History of the United States. Source: https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691003542/a-monetary-history-of-the-united-states-1867-1960

A Monetary History of the United States was a revolutionary book, providing insight into the Great Depression and why money matters. Prior to Friedman and Schwartz, economists did recognize the importance of monetarism, i.e., the belief that changes in the supply of money directly affect production, employment, and price levels within an economy.[13] Friedman and Schwartz’s research emphasizing the connection between monetary change and economic output converted economists into vehement supporters of monetarism.[14] A Monetary History is most famously remembered for its seventh chapter, “The Great Contraction”, in which Friedman and Schwartz depict the failure of the Federal Reserve (which was established to prevent a re-occurrence of the National Banking Era panics), to avert four major banking panics, resulting in a monetary collapse. The Federal Reserve’s lack of action as the banks failed, instilled panic in depositors (who were frightened of losing money deposited in failing banks) and spurred more bank runs, further exacerbating the economic crisis.[15] This ultimately led to the worst recession in the United States’ history.[16] In Chapter 7 of A Monetary History of the United States, Friedman and Schwartz assert that, “The contraction is in fact a tragic testimonial to the importance of monetary forces.” They demonstrate that “money matters”, by illustrating that the money-income relationship is crucial to changes in monetary arrangements and banking structures.[17] A key aspect of the money-income relationship is the evidence Friedman and Schwartz provide on monetary disturbances—declines in output were influenced by decreases in money supply (money supply consists of currency and multiple kinds of deposits held by the general public at commercial banks and other depository institutions), and instances of prolonged inflation were a result of the growth of money in excess of the growth of real income (income adjusted for inflation).[18]

The lessons taught by Friedman and Schwartz in A Monetary History of the United States have helped the Federal Reserve curtail other financial problems. The Great Inflation (1965-1982) was a period in which the United States experienced high inflation. Its origin is strongly attributed to the Federal Reserve’s policies (which were centered on attaining low unemployment) which resulted in excessive growth of the money supply.[19] These policies were reverted under Paul Volcker’s chairmanship of the Federal Reserve Board.[20] According to Bordo and Rockoff (2013), the slower monetary growth per unit of output appears to have contributed to the slowing of inflation from around 6 percent per year in 1965 to 2.4 percent per year from 1982 to 2008.[21] They claim that while the primary reason for the change in policy was a result of the public’s fear of inflation and the demand for action to curb it, the monetarist school of thought and Friedman and Schwartz’s work from A Monetary History of the United States deserves credit as well. In an interview with City Journal, Schwartz explains that throughout history, every instance in which the Federal Reserve created an excess of money (which can be done through maintaining extremely low interest rates or providing great liquidity to banks), resulted in rising prices. Although the increased money supply may appear to bolster consumers’ purchasing power initially, sellers within the economy increase prices to generate greater revenue. This leads to what Schwartz refers to as “manias”, when investors make riskier short-term investments in an attempt to surpass the expected inflation.[22] Ultimately, the lack of long-term investments for the riskier “manias” devastates entrepreneurship and hinders economic growth. In order to achieve steady economic growth while circumventing issues such as inflation, speculation, and recession, monetarists suggest creating predictability in the value of currency.[23] According to Schwartz, “The aim of policy should therefore be to establish predictable monetary rules that are easily understood, with full consideration of all the relevant costs and benefits.”[24] Schwartz was a strong supporter of the gold standard (she was the staff director of the U.S. Gold Commission in 1981 and 1982, whose purpose was to determine policy with respect to the role of gold in monetary systems); she recognized its benefit of long-term price predictability—which incentivizes agents to partake in long-term investments, a crucial component for the efficiency of a market economy.[25]

Bordo and Rockoff credit Schwartz and Friedman’s A Monetary History of the United States for some of the “improvement in policy” by the Federal Reserve in response to the 2008 Great Recession—as compared to its “response” during the Great Depression. They claim that the greater increase in the stock of money relative to output partially accounts for how mild the Great Recession was relative to the Great Depression. Under Bernanke, the Federal Reserve conducted substantial open market purchases, and may have been influenced by Schwartz and Friedman’s claim that the during the Great Depression the Federal Reserve should have been engaged in expansionary open market purchases.[26] Schwartz and Friedman appear to have strongly influenced Ben Bernanke. At Milton Friedman’s 90th birthday celebration in 2002, Bernanke said, “I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression, you’re right, we did it,…We’re very sorry, but thanks to you we won’t do it again.”[27] While Anna Jacobson Schwartz may have deserved credit for the Federal Reserve not repeating the detrimental errors it made during the Great Depression, she was a firm opponent of how Bernanke handled the Great Recession.[28] Schwartz believed that Bernanke responded improperly by flooding the market with money; she claimed a lack of liquidity was not related to or a cause of the financial crisis. She identified the “credit crunch” as the true cause of the recession, which stemmed from dwindling trust by the bankers in institutions seeking loans. Schwartz thought the lack of available credit arose because lenders were not able to properly identify who was solvent—i.e. which prospects had stable enough credit to make lending to them a safe bet. She supported the idea of buying bad assets from financial institutions at a reasonable price, so that the Federal Reserve would not inadvertently prop up failed institutions.[29] Schwartz saw Bernanke’s aggressive attempt to save bankers and directly bailout failing institutions as detrimental to the market and financial system as a whole. Schwartz believed that bad decisions should be punished and good decisions should be rewarded. She opposed Bernanke’s response so much that she wrote an Op-Ed in the New York Times (“Man without a Plan”) listing all of Bernanke’s mistakes, in a plea to have someone else appointed as chairman of the Federal Reserve.[30]

Anna Jacobson Schwartz was a brilliant economist, contributing extremely influential research to the field of economics. She was “one of those few economists who changed our understanding of the world.” Although she was disregarded by some and kept out of the spotlight, Anna was not deterred and conducted research into her 90s, adding profound studies that greatly altered her chosen field.

About the author:

Alec Franzese is a third-year Economics Major at the University of Chicago. His interest in researching Anna Jacobson Schwartz stems from a course he took at UChicago, Economic Policy Analysis. Schwartz was briefly mentioned at one point, and Alec was curious as to why he had never heard about her before, as compared to someone she worked so closely with, Milton Friedman. Outside of class, Alec is involved with the UChicago Open Ultimate Frisbee team. In his free time he partakes in his interests and hobbies, such as chess, scuba diving, and skiing.

References:

Featured Image: Wikimedia Commons

[1] Bordo, Michael B., Cecilia B. Conrad, Martin B. Feldstein, Alan B. Greenspan, Kevin B. Lang, Majorie B. McElroy, Edward B. Pasachoff, William B. Poole, James B. Poterba, Christina B. Romer, and Nancy B. Rose. “A Celebratoin of the Life of Anna Jacobson Schwartz.” American Economic Association’s Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession, 2013;

[2] Goldin, Claudia, Christina Romer, and Michael Bordo. “Women in Economics – Anna Schwartz.” Learn.mru.org. https://learn.mru.org/women-economics-series-anna-schwartz/#lp-pom-block-1049

[3] Goldin, Claudia, Christina Romer, and Michael Bordo. “Women in Economics – Anna Schwartz.” Learn.mru.org. https://learn.mru.org/women-economics-series-anna-schwartz/#lp-pom-block-1049; Hershey, Rober D., Jr. “Anna Schwartz, Economist Who Collaborated With Friedman, Dies at 96.” The New York Times. June 21, 2012. Hershey, Rober D., Jr. “Anna Schwartz, Economist Who Collaborated With Friedman, Dies at 96.” The New York Times. June 21, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/22/business/anna-schwartz-economist-who-worked-with-friedman-dies-at-96.html.

[4] Goldin, Claudia, Christina Romer, and Michael Bordo. “Women in Economics – Anna Schwartz.” Learn.mru.org. https://learn.mru.org/women-economics-series-anna-schwartz/#lp-pom-block-1049.

[5] Goldin, Claudia, Christina Romer, and Michael Bordo. “Women in Economics – Anna Schwartz.” Learn.mru.org. https://learn.mru.org/women-economics-series-anna-schwartz/#lp-pom-block-1049.

[6] Bordo, Michael B., Cecilia B. Conrad, Martin B. Feldstein, Alan B. Greenspan, Kevin B. Lang, Majorie B. McElroy, Edward B. Pasachoff, William B. Poole, James B. Poterba, Christina B. Romer, and Nancy B. Rose. “A Celebratoin of the Life of Anna Jacobson Schwartz.” American Economic Association’s Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession, 2013.

[7] Goldin, Claudia, Christina Romer, and Michael Bordo. “Women in Economics – Anna Schwartz.” Learn.mru.org. https://learn.mru.org/women-economics-series-anna-schwartz/#lp-pom-block-1049.

[8] Mahbuba, Dilruba, and Ronald Rousseau. “The Matthew Effect and a Relation with Concept Symbols and Defaults.” Annals of Library and Information Studies58 (December 2011). http://nopr.niscair.res.in/bitstream/123456789/13483/4/ALIS 58(4) 335-345.pdf.

[9] Nelson, Edward. 2004. “AN INTERVIEW WITH ANNA J. SCHWARTZ.” Macroeconomic Dynamics 8 (3). Cambridge University Press: 395–417. doi:10.1017/S1365100504030202.

[10] IBID

[11] Hershey, Rober D., Jr. “Anna Schwartz, Economist Who Collaborated With Friedman, Dies at 96.” The New York Times. June 21, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/22/business/anna-schwartz-economist-who-worked-with-friedman-dies-at-96.html.

[12] Bloomberg. “Anna Schwartz, Economist Milton Friedman’s Co-author, Dies at 96.” InvestmentNews. March 02, 2020. https://www.investmentnews.com/anna-schwartz-economist-milton-friedmans-co-author-dies-at-96-45166; Hershey, Rober D., Jr. “Anna Schwartz, Economist Who Collaborated With Friedman, Dies at 96.” The New York Times. June 21, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/22/business/anna-schwartz-economist-who-worked-with-friedman-dies-at-96.html.

[13] Britannica Academic, s.v. “Monetarism,”, https://academic-eb-com.proxy.uchicago.edu/levels/collegiate/article/monetarism/53341.

[14] Fettig, David. “Interview with Anna J. Schwartz.” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. September 1, 1993. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/1993/interview-with-anna-j-schwartz; Nelson, Edward. 2004. “AN INTERVIEW WITH ANNA J. SCHWARTZ.” Macroeconomic Dynamics 8 (3). Cambridge University Press: 395–417. doi:10.1017/S1365100504030202.

[15] Sorman, Guy. “Monetarism Defiant.” City Journal. January 27, 2016. https://www.city-journal.org/html/monetarism-defiant-13165.html.

[16] Bordo, Michael D., and Hugh Rockoff. “Not Just the Great Contraction: Friedman and Schwartz’s “A Monetary History of the United States 1867 to 1960″.” The American Economic Review 103, no. 3 (2013): 61-65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23469704

[17] Bordo, Michael D., and Hugh Rockoff. “Not Just the Great Contraction: Friedman and Schwartz’s “A Monetary History of the United States 1867 to 1960″.” The American Economic Review 103, no. 3 (2013): 61-65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23469704

[18]Bordo, Michael D., and Hugh Rockoff. “Not Just the Great Contraction: Friedman and Schwartz’s “A Monetary History of the United States 1867 to 1960″.” The American Economic Review 103, no. 3 (2013): 61-65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23469704; Schwartz, Anna J. “Money Supply.” Econlib; “Definitions for Real Income” What Does Real Income Mean? https://www.definitions.net/definition/real income.

;https://www.definitions.net/definition/real+income

[19] Bordo, Michael D., and Hugh Rockoff. “Not Just the Great Contraction: Friedman and Schwartz’s “A Monetary History of the United States 1867 to 1960″.” The American Economic Review 103, no. 3 (2013): 61-65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23469704

; Bryan, Michael. “The Great Inflation.” Federal Reserve History. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-inflation.

[20] Bryan, Michael. “The Great Inflation.” Federal Reserve History. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-inflation.

[21] Bordo, Michael D., and Hugh Rockoff. “Not Just the Great Contraction: Friedman and Schwartz’s “A Monetary History of the United States 1867 to 1960″.” The American Economic Review 103, no. 3 (2013): 61-65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23469704

[22] Bryan, Michael. “The Great Inflation.” Federal Reserve History. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-inflation.

[23] IBID

[24] Schwartz, Anna Jacobson. Money in Historical Perspective. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 1987. ECSCOhost.

- 266

[25] Schwartz, Anna Jacobson. Money in Historical Perspective. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 1987. ECSCOhost. p. 277 & 288

[26] Bordo, Michael D., and Hugh Rockoff. “Not Just the Great Contraction: Friedman and Schwartz’s “A Monetary History of the United States 1867 to 1960″.” The American Economic Review 103, no. 3 (2013): 61-65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23469704

[27] Hershey, Rober D., Jr. “Anna Schwartz, Economist Who Collaborated With Friedman, Dies at 96.” The New York Times. June 21, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/22/business/anna-schwartz-economist-who-worked-with-friedman-dies-at-96.html.

[28] Fettig, David. “Interview with Anna J. Schwartz.” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. September 1, 1993. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/1993/interview-with-anna-j-schwartz.; Sorman, Guy. “Monetarism Defiant.” City Journal. January 27, 2016. https://www.city-journal.org/html/monetarism-defiant-13165.html.

[29] Sorman, Guy. “Monetarism Defiant.” City Journal. January 27, 2016. https://www.city-journal.org/html/monetarism-defiant-13165.html.

[30] Schwartz, Anna Jacobson. “Man Without a Plan.” The New York Times. July 25, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/26/opinion/26schwartz.html.