By Maya Paloma ~

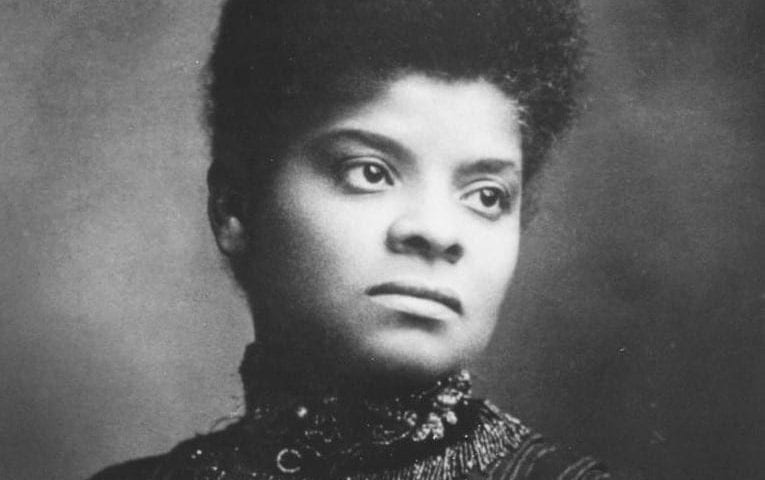

We owe it to Ida B. Wells to remember more than her name. We cannot forget her life, her story, which in so many ways profiles the ceaseless obstacles Black women faced in the last several decades and, all too often, still face today. More importantly, we ought not forget her perseverance for true societal change in the lives of Black people because that work is not over. Her portfolio of organizations, many of which are still in existence, with strong community presence and dedication to serving the needs of that community mirrors the shifting focus in activism today, and her relentless perseverance should be recognized for both its importance to movements in her time as well as a model for how people in positions of privilege ought to use their voices.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett never had an easy life, certainly not at the beginning of her life. She was born to her father Jim Wells—himself the son of his enslaver and an enslaved woman—and her mother Elizabeth Warrenton on July 16, 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Her parents met while they were enslaved to different masters. Her father’s father and master apprenticed him to a local carpenter, for whom her mother was a cook.[1] In Wells’ childhood, her mother recounted stories of beatings and harsh treatment while she was enslaved, but he only recalls a single instance in which her father referenced his time enslaved. When her father’s mother came for a visit, she told him that his former master’s wife wanted to see him and his children. Wells recalls his words exactly, “I never want to see that old woman as long as I live. I’ll never forget how she had you stripped and whipped the day after the old man died, and I am never going to see her. I guess it is all right for you to take care of her and forgive her for what she did to you, but she could have starved to death if I’d had my say-so. She certainly would have, if it hadn’t been for you.”[2] In reading Wells’ work, I find that her father’s sentiment in this moment must have been one of the most impactful moments in her life that guided her throughout her career.

I find that another moment must have been a turning point as well: the death of her parents. Both of Wells’ parents died within a day of each other due to a yellow fever epidemic that gripped Mississippi and Holly Springs,[3] leaving a sixteen-year-old Ida to care and provide for her five younger siblings.[4] She quickly began working as a teacher at a country school, then moved to Memphis with her two youngest sisters, leaving her other siblings in the care of family and friends, with intentions to become a city schoolteacher for a higher salary.[5]

At the age of twenty two, Wells won a court case against the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad for damages totalling five hundred dollars after she was forced out of her seat in the ladies’ car and into the smoking car, even though the railroads were still unsegregated at the time. The lower court ruling was later overturned by the Mississippi Supreme Court, but she later reflected that it was imperative for the state to refute the implications of her victory in court by overturning the verdict. She explains, “The gist of that decision was that Negroes were not wards of the nation but citizens of the individual states, and should therefore appeal to the state courts for justice instead of to the federal court. The success of my case would have set a precedent which others would doubtless have followed.”[6] Although she explains that it took her a number of years to come to this realization, I find that this reflection succinctly captures the solid wall of systemic racism Ida B. Wells and her contemporaries strove to break down, and is, in many ways, the same wall we continue to dismantle.

Wells’ career of activism truly began in 1889 after she was fired from her job as a Memphis school teacher. She had written a number of articles in Black newspapers critical of the Memphis school system, and was subsequently fired, leading her to fully devote herself to her journalistic career.[7] Wells explains in her autobiography that she knew losing her job as a teacher was a possibility following her critical articles, “but I had taken a chance in the interest of the children of our race and had lost out.”[8]

The paper Wells went on to write for, the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight, was described as “a helpful influence in the lives of our people”[9] across multiple states and took stands on local and national issues. For example, the Free Speech criticized Memphis ministers after they protected a fellow minister caught for adultery and Wells herself wrote an editorial critiquing Booker T. Washington’s claim that “‘two-thirds of the Negro preachers of the south were morally and intellectually unfit to teach or lead the people.’”[10]

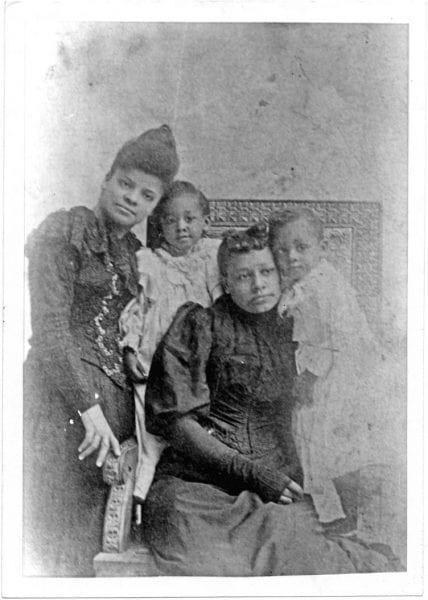

Ida B. Wells, standing left, with Maurine Moss, widow of Thomas Moss, lynched in Memphis March 9, 1892, with Tom Moss Jr. Wells, Ida B. Papers, (Box 10, Folder 1). Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

As Wells and Free Speech grew the reach of their influence, one final turning point truly catapulted Wells into activism: the 1892 lynching of three black men in Memphis. Thomas Moss opened the People’s Grocery Store with two friends, Calvin McDowell and Henry Stewart, that competed directly with a white-owned grocery store that had been the only available grocery store up to that point in a predominantly Black suburb of Memphis. In Wells’ description of the events leading up to the lynching, the conflict began over a game of marbles won by a Black boy. Moss was told by Memphis police that he had to protect the People’s Grocery on his own when the fight over marbles escalated into a threat on his store. So Moss and his colleagues armed men to guard the back entrance, who shot at a group of armed white men they saw stealing merchandise through the door into the back room of the store. Three of the men protecting the People’s Grocery were killed, in addition to Moss, McDowell, and Stewart, who were taken to an empty field and executed.[11]

Wells herself was out of town when the lynching occurred, but the moment she arrived back in Memphis, she and the Memphis Free Speech published a statement for the Black community there. The statement was a call to action, reading, “There is therefore only one thing left that we can do; save our money and leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons.”[12] The effects of the Black community’s mass refusal to support the Memphis economy was immediately felt by people in high places. Wells recalled a plea from leaders of the City Railway Company for her to ask Black patrons to return to using the railway because, “colored people had been their best patrons.”[13] She steadfastly refused their reply, and instead she published her conversations with the City Railway leaders and encouraged Black readers to continue saving their money to leave Memphis.[14]

Just as Wells’ journalistic activism had threatened her livelihood before, so now it threatened her career and even her life. While she was in Philadelphia at a conference, a group of white men ran the co-owner of the Memphis Free Speech newspaper out of town, destroyed the newspaper’s office, and left a note with a threat: “anyone trying to publish the paper again would be punished with death.”[15] Again, just as Ida B. Wells had pivoted gracefully from teaching to journalism, so she pivoted from work in Memphis to work in New York after she received word from friends in Memphis that her house and the trains were being watched by white men with instructions to kill her on sight.[16]

Wells continued to focus on the specific needs of Black communities in her work in Chicago. Wells was a key founder of Black women’s clubs across the city, including one of, if not the, first Black women’s clubs called the Ida B. Wells Club in 1893.[17] These first clubs were centered around charity and volunteering in addition to courses like literature and music.[18] Their club aims followed in line with the motto of the National Association of Colored Women and the National Association of Colored Womens’ Clubs, “Lifting as we climb.”[19] As women began protesting for the vote in the early twentieth century, suffrage clubs began to spring up around Chicago and the country at large. Ida B. Wells herself founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in 1913, the first of its kind for Black women in the United States.[20][21] The Alpha Suffrage Club met both at Bridewell Penitentiary, where they supported female inmates, and at the Negro Fellowship League,[22] which was formed out of an impromptu meeting of young Black men at Wells’ own home.[23] Wells addressed the need for community spaces like the Negro Fellowship League for the Black community in Chicago in a speech at a dinner, “[O]urs is the most neglected group. All other races in the city are welcomed into the settlements, YMCA’s, YWCA’s, gymnasiums and every other movement for uplift if only their skins are white. The occasional black man who wanders uninvited into these places is very quickly given to understand that his room is better than his company.”[24] This quotation emphasizes Wells’ awareness of the importance of smaller, community-based organizations that intimately understands the immediate needs of community members. This is in stark contrast to the broad-scale social change larger organizations like the NAACP held at their core.

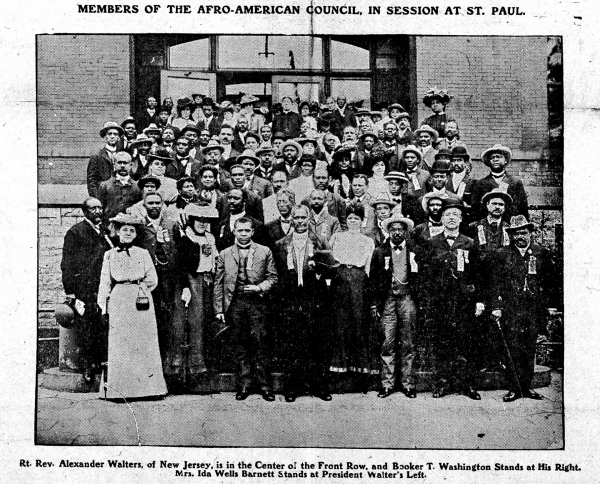

Wells has a tangled history with the NAACP. Wells, among numerous other recognizable Black and white figures from the Progressive Era, was present at the forty-person committee meeting that would become the NAACP. At the close of the meeting, W.E.B. DuBois had the honor of reading the roll call for all those present, and although Wells should have been included, her name was notably absent. She writes, “Then bedlam broke loose.”[25] A friend of Wells, John Milholland, found her as she began to leave the building and explained that when he had handed the list over to DuBois, her name was still included. Eventually, DuBois admitted that he figured she could be well enough represented through the inclusion of a woman Wells had traveled to the meeting in New York with. He then “took the liberty of substituting” Wells’ name for the name of a male dentist who would otherwise have been left off the roster.[26] When he, and many others, offered to have her name added to the roster before it went to print in the newspapers the next morning, she refused outright, explaining that she wouldn’t have DuBois’ intentional This incident, at the very founding of the NAACP, was just the beginning of tension between the organization and Wells.

As the NAACP developed, Wells took issue with both the leadership and the apparent values of the organization. Firstly, Wells seemingly attributed virtually all shortcomings of the organization to the chairman of the executive committee, Mary White Ovington, a white woman. I find that it is only appropriate to quote Wells directly here:

“It is impossible for her to visualize the situation in its entirety and to have the executive ability to seize any of the given situations which have occurred in a truly big way. She has basked in the sunlight of the adoration of the few college-bred Negroes who have surrounded her, but has made little effort to know the soul of the black woman; and to that extent she has fallen far short of helping a race which has suffered as no white woman has ever been called upon to suffer or to understand.”[27]

Further, Wells rejected DuBois’ position that power ought to be reserved for college-educated elite men and grew increasingly distant from the NAACP as similar values seemed to encroach on the organization’s activism.[28]

As Wells fell out with the organization and its leaders, she returned to the communal, grassroots organizations and activism she had spent so much of her career working for. She expanded the role of the Negro Fellowship League[29] and led the Alpha Suffrage Club in registering voters for municipal Chicago elections and canvassing predominantly Black neighborhoods.[30] It truly began in her role in Memphis as a journalist, where she put her job on the line twice—and her life, in the second instance—for the sake of honest, powerful reporting. She prioritized the activism that best served her community even when it was at her personal detriment. Still, she never stopped working toward her goal of social change. She demanded equal recognition and appreciation of her work and efforts, even when she had to face down prominent figures like W.E.B. DuBois and mobs of white men, and for that, we ought to recognize and remember her work, her life, and her activism.

About the author:

Maya Paloma is a Creative Writing major at the University of Chicago, Class of 2022. She was first drawn to study Ida B. Wells-Barnett for the Illinois State History Fair in 2017 and has only found Wells-Barnett’s life to be more meaningful as time has gone on and social values continue to change. Maya believes in the power of the act of writing and reading, something she bring to both her creative and academic writing. She believes that if we have the honor to be read by others, we ought to use that opportunity to tell important stories, and as readers, we have a responsibility to seek and witness the stories of others.

References:

[1] Ida B. Wells, Crusade for Justice, ed. Alfreda M. Duster (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), 7-8.

[2] Wells, Crusade for Justice, 9-10.

[3] Wells, Crusade for Justice, 10-11.

[4] Ochiai, Akiko, “IDA B. WELLS AND HER CRUSADE FOR JUSTICE: An African American Woman’s Testimonial Autobiography,” Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal 75, no. 2/3 (1992): 366.

[5] Wells, Crusade for Justice, 18.

[6] Wells, Crusade for Justice, 18-20.

[7] Ochiai, “Ida B. Wells and her Crusade for Justice,” 366.

[8] Wells, Crusade for Justice, 37.

[9] Wells, Crusade for Justice, 40.

[10] Wells, Crusade for Justice, 40-41.

[11]Wells, Crusade, 48-50.

[12] Ibid, 52.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid, 52-55.

[15] Ibid, 61-62.

[16] Ibid, 62.

[17] Knupfer, Anne Meis. The Chicago Black Renaissance and Women’s Activism. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006), 93.

[18] Knupfer, Anne Meis. “‘Toward a Tenderer Humanity and Nobler Womanhood’: African-American Women’s Clubs in Chicago, 1890-1920.” Journal of Women’s History 7, no. 3 (1995): 58-76.

[19] Ibid, 62. and National Association of Colored Womens’ Clubs. “History.” http://nacwc.org/history. Accessed 12/12/2020

[20] Knupfer, “African-American Women’s Clubs,” 68.

[21] Pich, Hollie. “Various, Beautiful, and Terrible: The Life and Legacy of Ida B. Wells-Barnett.” Australiasian Journal of American Studies 34, no. 2 (2015): 59-74.

[22] Knupfer, “African-American Women’s Clubs,” 68.

[23] Wells, Crusade for Justice, 299-300.

[24] Ibid, 301-302.

[25] Wells, 323-324.

[26] Ibid, 325.

[27] Ibid, 327-328.

[28] Pich, 63-64.

[29] Wells, 330.

[30] Knupfer, “African-American Women’s Clubs,” 69-70.