By Harshil Jain ~

Born to high-caste Brahmin in India in 1858, Pandita Ramabai was fully immersed in orthodox Hindu religion from the outset, yet was raised by her father with very unconventional beliefs for the time period. During an era where even the slightest education for women was looked down upon by society as a waste of time, tradition, and resources, Ramabai was taught Sanskrit by her father – an ancient Hindu script reserved solely for highly educated men.

The Hindu religion was all Pandita and her family knew; they believed it was entirely sufficient for life and culturally proper according to their high caste.

“Our parents had unbounded faith in what the sacred books said. They encouraged us to look to the gods to get our support”.[1]

However when the Great Famine of ‘76-’78 raged the Indian countryside, resulting in the starvation and death of her parents and sister, Ramabai (age 16) was left with the realization that the only reliable source of protection and sustenance comes from oneself. Disillusioned, Ramabai would spend the next few years wandering over 4,000 miles from village to village, growing more and more convinced that the current social structure was one that was radically flawed.

The independence that Pandita Ramabai gained during her years as an orphan proved to be a seed of blessing wrapped in a curse. This unique combination of an educated childhood coupled with unrestrained freedom past adolescence allowed Ramabai to escape the shackles of required marriage that was conventionally forced upon women by the time they reached the birth-giving age of 13-14, sometimes even younger. She was further angered by the fact that despite the act of childbirth being conducted by women, there was not a single female who was allowed to pursue higher education specializing in a medical field. Furthermore, decisions concerning conception and birth were solely decided by the males of a family, and childbirth-related procedures were performed in many rural settings by male doctors that clearly had inferior knowledge about the workings of the female reproductive system – resulting in a high mother-infant mortality rate.

After being denied admission into a medical college in 1883 in both India and Britain, Ramabai began to push for women-only education programs and the medical education of women, as “the situation in India was that women’s conditions were such that women could only medically treat them”.[2] This was largely in the hopes that with female medical professionals, women giving birth could be given proper medical advice to prevent complications during birth and the death of newborns due to uneducated superstition.

After her successive rejections from medical institutions due to the clear basis of gender discrimination, Ramabai would later write, “In ninety-nine cases out of a hundred the educated men of this country are opposed to female education and the proper position of women. If they observe the slightest fault, they magnify the grain of mustard-seed into a mountain, and try to ruin the character of a woman”.[3] Thus was the birth of the fundamental belief that would spur forth multiple decades of feminism-related movements and activism: Women needed social independence. Ramabai’s core ideas centered around being able to eventually develop the mindset of all women so that they would have the ability to live independently from men, and have the ability and confidence to pursue skilled work and opportunities.

The first issue that Ramabai encountered was the vastly differentiated treatment men gave to women, as opposed to the treatment women gave to men. During her travels across rural India, Ramabai mentions the typical circumstance of a family.

“The girl now belongs to the husband’s clan; she is known by his family name, and in some parts of India the husband’s relatives will not allow her to be called by the first name that was given her by her parents; henceforth she is a kind of impersonal being. She can have no merit or quality of her own. The wife is declared to be the ‘marital property’ of her husband, and is classed with ‘cows, mares, female camels, slave-girls, buffalo-cows, she-goats and ewes’”.[4]

Treated simply as objects, most mothers and wives were inevitably reduced to two roles under the domineering nature of a solely male-driven society: as child bearers and housekeepers. It was not uncommon that if a woman failed in the performance of either of these two categories, they would be cast out of their marriage or their family and replaced, with the blame of the ordeal resting on the shoulders of the woman. What they ate, what they cooked, what they wore, where they went, who they conversed with; nearly every decision in a woman’s life was made by a husband or a father. In such a society, where an entire gender was reduced to the role of an automaton, any chance to break away from the oppressive patriarchal society is taken away and crushed through a combination of lack of opportunity and social brainwashing. It becomes impossible to hope for a life of freedom and choice when one doesn’t even know such a reality can exist.

The second issue Ramabai hoped to combat was one that stemmed from the previous one. Although the British had set the minimum age of marriage for women at fourteen, this could only be enforced in larger towns and cities.

“Girl brides became younger towards the Medieval period, and it became increasingly common for girls as young as six or eight to be married as Indian society”.[5]

The goal in such occurrences tended to be geared towards economic gain for the males in a family. By treating female children as simple tokens, they were traded through marriage in exchange for financial support, political power, or as a way to settle debts – economic or social.

Furthermore, many families would see daughters as a waste of resources, whereas a son could eventually support the family.

“In a home shadowed by adherence to cruel custom and prejudice, a child is born into the world; the poor mother is greatly distressed to learn that the little stranger is a daughter, and the neighbors turn their noses in all directions to manifest their disgust and indignation at the occurrence of such a phenomenon. The mother, who has lost the favor of her husband and relatives because of the girl’s birth, may selfishly avenge herself by showing disregard to infantile needs and slighting babyish requests. If a girl is born after her brother’s death, or if, soon after her birth, a boy in the family dies, she is in either case regarded by her parents and neighbors as the cause of the boy’s death. She is then constantly addressed with some unpleasant name, slighted, beaten, cursed, persecuted and despised by all”.[6]

Such treatment would imprint upon a daughter the belief of their inferiority compared to males, and through child marriage would result in a wife who sincerely believes the best she can do is listen to her husband’s every command and in time produce a male child. Pandita Ramabai came to realize that in order to successfully separate women from the restraints imposed by the males in their family, their mindset had to be tempered towards a progressive goal from childhood, before social brainwashing could deprive them of a belief in gender equality. After witnessing the sad cycle of hopelessness and mistreatment of wives and daughters, she hoped that the education of women could allow women to break their children away from their dependance on the males of society, giving a chance for the next generation of daughters to grow up free from the shackles of male-dictated tradition and instead have the freedom and independence to forge their own path.

Ramabai’s bid to provide female Indians with social independence through the end of child marriage was broadened in 1882 following the death of her husband, causing Ramabai to suffer the brand of widowhood – one of the most dreaded titles a woman could possess.

“The problem with enforced widowhood was that it not only caused individual widow’s suffering, it also led to social problems of major proportions. Such conditions as adultery, incest, polygamy, prostitution, abortions, and the birth and murder of illegitimate infants became associated with the widows”.[7]

Ramabai’s greatest concern with widowhood, along with child marriage, was the practice of Sati, practiced in certain regions across India.

“The self-immolation of widows on their deceased husband’s pyre was evidently a custom invented by the priesthood after the code of Manu was compiled. It is very difficult to ascertain the motives of those who invented the terrible custom of the so-called Suttee [Sati], which was regarded as a sublimely meritorious act. As Manu the greatest authority next to the Vedas did not sanction this sacrifice, the priests saw the necessity of producing some text which would overcome the natural fears of the widow as well as silence the critic who should refuse to allow such a horrid rite without strong authority”.[8]

With the age difference between wife and husband commonly being a decade, sometimes even more, Ramabai was horrified to learn and witness the burnings of widows as young as twenty or thirty years old, most of whom wished to live but were denied the right due to their title of a widow. Ramabai, in speeches across the US on the rights of widows, would later express multiple times how thankful she was that the town where she was married did not also practice Sati.

It greatly concerned Ramabai that it was even other women who treated widows as vermin, when in her eyes all women should band together in a bid for greater rights. A common theory by Ramabai was that due to the oppression of most women by their husbands and fathers, their desire for a feeling of superiority led to their mistreatment of widows. This was further deemed to be both morally and socially correct due to the treatment of widows by males, coupled with the inherent helplessness of the common widow.

To combat the fate of widows, Ramabai founded the Ministry among Destitute & Orphan girls in 1889 and the Mukti Mission in 1900, whose goal was to take in widows, orphans, abandoned daughters, and the blind in order to teach them to be self-sufficient and independent through education and the creation of a social environment where it was taught that the rights of women cannot be discarded.

She found great support in her endeavor during her trips to the US to raise additional funding for the establishment of Ramabai’s foundations, with a common recipient of her speeches and requests being the Women’s Christian Temperance Union during the late 1880s and early 1890s.

“The United States, where she went after England to raise money for the widows’ home she established in Bombay in 1889, was more hospitable, at least where financial support for her reform projects were concerned”.[9]

There, she met many women who were equally passionate about the need of greater women’s rights – the progenitors of the future women’s suffrage and feminist movements. Ramabai was greatly inspired by the power that could be mustered when an entire gender banded together to combat a singular belief, and she hoped that Indian women could similarly muster the joint conviction and courage for such a movement. It was a meeting with Harriet Tubman that especially inspired Ramabai; who in a letter wrote to her daughter that she wished her to be “as helpful to her own dear countrywomen as Harriet was and is to her own people”.[10]

Ramabai would continue to tour India, the US, and Britain, giving speeches about the need for social reform and independence for women for the next 20 years until her death on April 22, 1921. During that time, she would be hailed in a multitude of feminist activist circles across the US as the Seed of the Women’s Uplift Movement in India.

Her initial goal for an infusion of women into specialized medical fields gained great traction in the late 1890s and early 1900s in Britain, eventually reaching the ears of Queen Elizabeth, who also showed approval of the undertaking. Ramabai’s ideas were eventually brought to life by the Women’s Medical Movement in the early 1900s by Lady Dufferin, who was inspired by the ideals imbued in Ramabai’s activist speeches and created The Fund, which supplied scholarships for the medical education (medical tuition) of women in India.

This was due to her firm belief that “Scientists, more than most men, require an expressional medium which shall enable them to pool all their knowledge, which shall enable them to give and take all facts at will”.[11] With penetration into the medical field by women, it would eventually become easier for women in India to expand into other science-oriented fields, eventually setting a new, more equalized, societal norm.

About the Author:

My name is Harshil Jain and I am an undergraduate at the University of Chicago. I am currently pursuing a degree in Physics and Economics, with a specialization in Data Science. I am very extroverted and I love hiking, biking, playing tennis, and generally any outdoor-related activity that I can enjoy with my friends. While I have a tendency to be very logical and analytical in my thinking, I like to believe that I am also a pretty funny guy (or at least my friends tend to think so). It is my belief that the neglect of many great female historical figures deprives future generations of valuable knowledge, and in order for society to progress as quickly and efficiently as possible, we must make use of all the learnings of influential figures of the past, regardless of gender or race.

References:

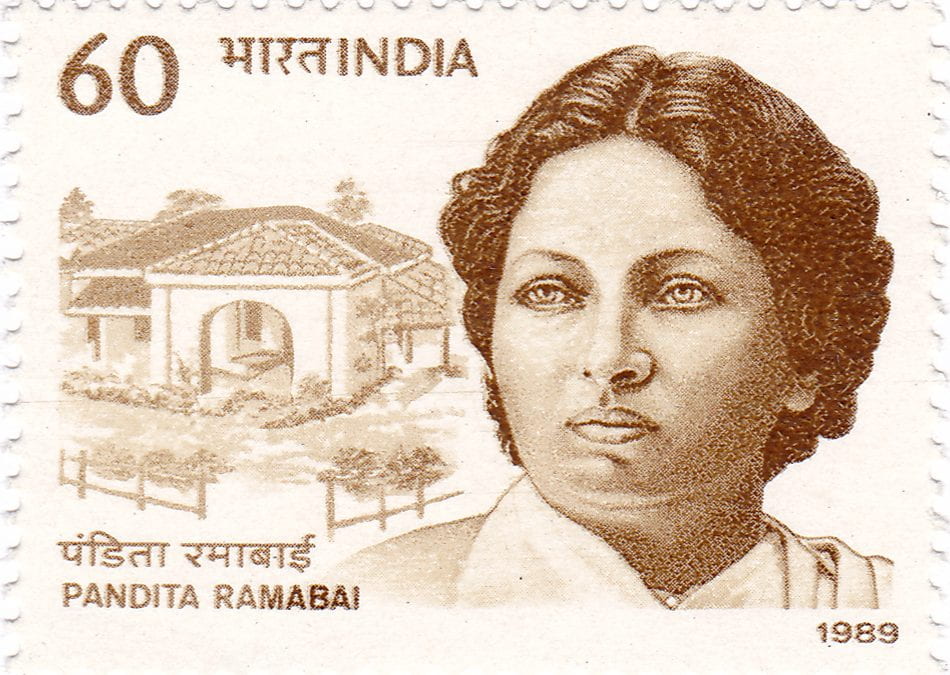

Featured Image: Pandita Ramabai on the 1989 stamp of India. Source: India Post, Government of India, GODL-India https://data.gov.in/sites/default/files/Gazette_Notification_OGDL.pdf

[1] Kosambi, Meera. Pandita Ramabai through Her Own Words: Selected Works. New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2000.

[2] Ramabai, Pandita. The Life Story of Pandita Ramabai: A Testimony. 2nd ed., 142 Victoria Street, Footscray, Franklin Press, 1946.

[3] Sarasvati, Pundita. High Caste Hindu Woman. First edition, 10th thousand., PANDITA RAMABAI SARASVATI, 1888.

[4] Sarasvati, Pundita. High Caste Hindu Woman. First edition, 10th thousand., PANDITA RAMABAI SARASVATI, 1888.

[5] Marion, Aparna. “History of Child Marriage in India.” Terres d’Asie, Oct. 2010, terredasie.com/english/english-articles/history-of-child-marriage-in-india.

[6] Sarasvati, Pundita. High Caste Hindu Woman. First edition, 10th thousand., PANDITA RAMABAI SARASVATI, 1888.

[7] Singh, Priyam. “Women, Law, and Criminal Justice in North India: A Historical View.” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, vol. 28, no. 1, 1996, pp. 27–38. Crossref, doi:10.1080/14672715.1996.10416184.

[8] Sarasvati, Pundita. High Caste Hindu Woman. First edition, 10th thousand., PANDITA RAMABAI SARASVATI, 1888.

[9] Burton, Antoinette. “Restless Desire.” At the Heart of the Empire: Indians and the Colonial Encounter in Late-Victorian Britain, First, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1998, pp. 72–109.

[10] Ramabai, Pandita, and Meera Kosambi. Pandita Ramabai’s American Encounter: The Peoples of the United States (1889). Indiana University Press, 2003.

[11] Vaughan, Kathleen O.. “THE COUNTESS OF DUFFERIN’S FUND.” British Medical Journal vol. 2,2494 (1908): 1219–1220.

Bibliography:

- Burton, Antoinette. “Restless Desire.” At the Heart of the Empire: Indians and the Colonial Encounter in Late-Victorian Britain, First, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1998, pp. 72–109.

- Butler, Clementina. Pandita Ramabai Sarasvati; Pioneer in the Movement for the Education of the Child-Widow of India. New York, Ulan Press, 2012.

- India Post. “Pandita Ramabai 1989 Stamp of India.” Wikimedia Commons, Government of India, 26 Aug. 1989, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pandita_Ramabai_1989_stamp_of_India.jpg.

- Khan, Aisha. “Overlooked No More: Pandita Ramabai, Indian Scholar, Feminist and Educator.” The New York Times [New York, New York], 15 Nov. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/11/14/obituaries/pandita-ramabai-overlooked.html.

- Kosambi, Meera. Pandita Ramabai through Her Own Words: Selected Works. New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Marion, Aparna. “History of Child Marriage in India.” Terres d’Asie, Oct. 2010, terredasie.com/english/english-articles/history-of-child-marriage-in-india.

- Ramabai Sarasvati, Pa High Caste Hindu Woman. First edition, 10th thousand., PANDITA RAMABAI SARASVATI, 1888.

- Ramabai Sarasvati, Pandita. “Pandita Ramabai Sarasvati 1858-1922 Front-Page-Portrait.” Wikimedia Commons, Press of the J. B. Rodgers printing co., 1922, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pandita_Ramabai_Sarasvati_1858-1922_front-page-portrait.jpg.

- Ramabai Sarasvati, Pandita. The Life Story of Pandita Ramabai: A Testimony. 2nd ed., 142 Victoria Street, Footscray, Franklin Press, 1946.

- Ramabai Sarasvati, Pandita, and Meera Kosambi. Pandita Ramabai’s American Encounter: The Peoples of the United States (1889). Indiana University Press, 2003.

- Singh, Priyam. “Women, Law, and Criminal Justice in North India: A Historical View.” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, vol. 28, no. 1, 1996, pp. 27– Crossref, doi:10.1080/14672715.1996.10416184.

- Vaughan, Kathleen O.. “THE COUNTESS OF DUFFERIN’S FUND.” British Medical Journal 2,2494 (1908): 1219–1220.