By Parysa Mostajir ~

When scholars discuss the pragmatist theory of democracy, Jane Addams is not usually the first name to arise. More often, writers turn to the works of her close friend and intellectual kindred, John Dewey, such as his 1916 work, Democracy and Education. Jane Addams’ name is more commonly mentioned in association with the practice or application of pragmatist ideas. Addams spent her life embroiled in the battles of the labor movement, serving on national and international committees for labor rights, lobbying for legislative protection of laborers, mediating trades unions strikes, and providing educational and childcare services to immigrant working populations through Hull-House, the settlement she founded and directed in the Near West Side neighborhood of Chicago. This active, non-academic work was her highest priority, as she made clear in a letter to her editor in May of 1901. She despaired that she had found no time to write, but concluded that “Hull-House is of more importance.”[1]

But while Addams spent a great deal of her life in action, there are good reasons to resist the interpretation of her as contributing to pragmatism only through the application of others’ theories. Firstly, this is an old, familiar narrative. In the early twentieth century, when women were usually denied academic employment at universities, they typically conducted academic work in hybrid academic-social institutions such as Hull House settlement. Their male contemporaries, who held positions as university professors, collaborated extensively with such settlements and their majority-female staff. But despite the groundbreaking and original theoretical works (like Hull House Maps and Papers) which were published by members of such institutions, male professors often viewed them as merely instrumental for accumulating data and testing their own theories.[2] To inherit this outdated interpretation without extensive justification would be both ethically and epistemically irresponsible.

The second reason to resist the interpretation of Addams as an exclusively applied pragmatist comes when we look to the historical record and find that this narrative is inconsistent. Remarkably, among all her commitments, Addams found time to write a great deal on an impressive range of topics, including the topic of democracy. Dewey was familiar with Addams’ writings to the point that he assigned them as class readings to his students as early as 1902. And although she rarely is credited with contributing to the development of the pragmatist theory of democracy, in a lecture series at the University of Chicago fourteen years before he published Democracy and Education, Dewey attributed to Addams the first definite statement of the pragmatist thesis “that democracy means certain types of experience,—an interest in experience in its various forms and types.”[3] This attribution of credit for the development of the pragmatist theory of democracy is supported by Dewey’s daughter’s statement that her father’s beliefs in democracy “took on both a sharper and deeper meaning because of Hull House and Jane Addams.”[4] Addams’ Democracy and Social Ethics and Twenty Years at Hull House confronts its readers with a radical theory of democracy that, though similar in its foundational ideas to that of Dewey, is indeed sharpened and deepened by being embedded in the social and political struggles of making democracy work. No understanding of the pragmatist theory of democracy, nor an honest account of its origins, can therefore be complete without considering Addams’ writings on the subject.

The best place to find Addams’ contribution to the pragmatist theory of democracy is her 1902 book, Democracy and Social Ethics, since it garnered widespread admiration not only broadly, but specifically among contemporary pragmatist thinkers. For example, William James, a prominent early-twentieth century pragmatist, described Democracy and Social Ethics as “one of the great books of our time,” and recommended Addams’ work highly to his academic colleagues.[5] In this book, Addams states three connected theses that characterize the pragmatist theory of democracy:

- Democracy is a feature of human activity;

- Democracy is a rule of living;

- Democracy is to be achieved by exposure to the diverse experiences of one’s social counterparts.

Firstly, democracy was not an inanimate political institution, but a feature of human activity. Addams complained that “well-to-do portions of the community are prone to think of politics as something off by itself,” and the same abstraction and distance was true of many people’s notions of democracy.[6] According to Addams, it was not enough for democracy to be compartmentalized as the existence of a particular system of voting, with citizen participation reduced to filling out a ballot once every few years. Democracy needed to be extended beyond the compartmentalized ‘political’ sector to every arena of human activity. For example, Addams complains that the relationships between the “benefactor and beneficiary” of charity work, or between the factory owner and factory workers in the industrial sector, have not sufficiently absorbed and applied the lessons and methods of democracy.

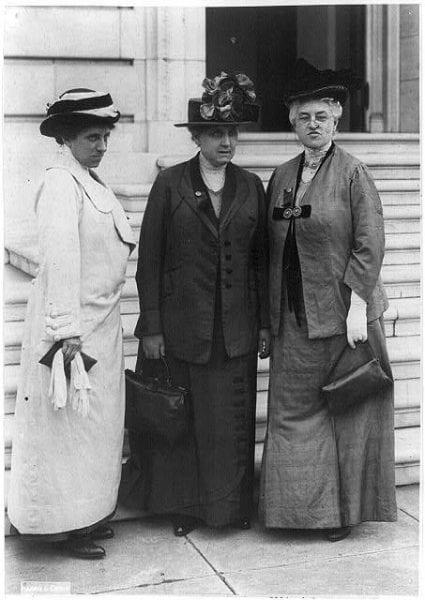

Jane Addams (center) with fellow settlement-workers, Julia Lathrop (left) and Mary McDowell (right), on a suffrage mission on Capitol Hill, 1913. Photo by Harris & Ewing. Source: cph 3a50129, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Secondly, democracy is neither “a sentiment” nor “creed,” but “a rule of living.”[7] This is related to the centrality in pragmatist philosophy of practice. While democracy was based on certain principles or beliefs, like freedom of expression and association, its actual existence was played out in habitual interactions and relationships between people in a society. Addams’ “newer conception of Democracy” involved not a reframing of the analytic principles and theories of an ideology, but the extension of democratic obligations into everyday life in the form of “new line[s] of conduct.”[8] As a rule of living, these lines of conduct needed to be cultivated and exercised as habits of engagement, to constitute a stably democratic society. Addams’ suggestion was that we need to break out of our old moral habits, and educate citizens into new, second-nature democratic-interactive dispositions towards each other.

Thirdly, these dispositions and habits were to be constituted by continual “mixing” of groups, and consequent familiarity with “diversified human experience.”[9] While society was stratified and socially segregated—into rich and poor, factory owner and factory worker, American and immigrant, white and black—Addams argued that the realization of democratic society was impossible. She claimed that “much of the insensibility and hardness of the world is due to the lack of imagination which prevents a realization of the experiences of other people.”[10] That is, our attitudes towards other people and their problems—including social, economic, and political issues affecting certain classes of society—were heavily dependent on our exposure to the lived experiences of people encountering these problems. If we “see the size of another’s burden,” we are more likely to have a liberal and favorable attitude towards reform efforts being made on their behalf.[11] This is because, Addams claimed, it is from a “common fund of memories and affections” that our sense of “obligation naturally develops” towards other people.[12]

Addams’ hypothesis has since been demonstrated in social-psychological studies. For example, it is now well known that an individual’s acceptance or tolerance of homosexuality is positively correlated with that person having a friend or acquaintance who is gay, lesbian, or bisexual. Our own exposure to other people’s very different experiences “determine our understanding of life” and consequently determine “the scope of our ethics.”[13] To have a democratic society in which the institutions we share—like laws, economic policies, cultural norms—are representative and inclusive of the needs and desires of its diverse members, we must cultivate a disposition of curiosity and an ethic of mutual understanding between diversely situated people, by bringing citizens into habitual contact with different types of people with different needs, desires, and interests. “[D]iversified human experience and resultant sympathy,” Addams declared, “are the foundation and guarantee of Democracy.”[14]

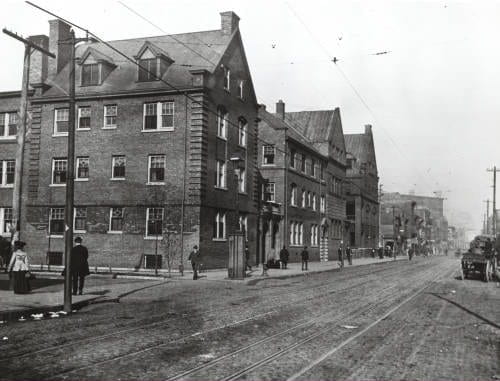

Exterior of Hull-House building complex, c. 1900. Source: JAMC_0000_0135_0156, Seven Settlement Houses digital image collection, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Addams demonstrates the importance and relevance of her radical conception of democracy using the example of charity work. In her work among immigrants in Chicago, Addams would often encounter charity workers who considered themselves as ‘doing good’ by providing aid to poor families. They would arrive from their wealthy parts of town to distribute resources which they themselves had selected as necessary and appropriate for the lives of industrial workers living in the poorer areas of Chicago. They tended to impose their own middle-class values of thrift and temperance. For example, they might refuse to purchase fine clothes for the family, encouraging them to wear modest clothes more suited to their means. However, because such charity workers were unfamiliar with the experiences of this poor family, they would fail to understand that, unlike their own experiences in their own social circles, a young woman in a poor family “is judged largely by her clothes.” Therefore, “if social advancement is her aim, [purchasing nice clothes] is the most sensible thing she can do.”[15] Addams argues that “[b]ecause of this diversity of experience, the visitor is continually surprised” by the standards and needs of the people she tries to help.[16] The problem she is encountering is the lack of democratic values structuring her behavior towards the very different group she is interacting with. In order to truly help people, the first step must be sharing in their experiences and coming to understand their lives, cultures, needs, and desires. This is a major reason why Addams conducted reform work from within a settlement house. Women at Hull House resided in the same neighborhood as the people to whom they offered services, and so they became democratically familiar with the experiences of their neighbors. Hull House was a democratically-structured charity institution, and the charity work was conducted through democratic rules of living.

Resident houses were, of course, not the only way of democratically organizing institutions or encouraging democratic ways of life. Addams describes the policy of dividing “a proportion of the profits at the end of the year among the employees” of a factory as a “democratic effort,”[17] as well as “calling upon the workmen either for self-expression or self-government,” gesturing towards the connection between democratic society and a co-operatively structured economy.[18] She also mentions the importance of newspapers and literature in enabling people “to see farther, to know all sorts of men” and providing “preparation for better social adjustment,” reflecting the importance of literacy and the press in a democratic society.[19] In Twenty Years at Hull House, she discusses the democratic potential of art in allowing people to come to understand the experiences of a diversity of people. For example, in Hull House’s English literature classes, one recent Jewish immigrant composed a portrayal of “the Jewish day of Atonement, in such wise that even individualistic Americans may catch a glimpse of that deeper national life which has survived all transplanting.”[20] In all these institutions and practices, experiences are being communicated between diverse members of a society and incorporated into shared understandings.

Cultivating a democratic society required not just nurturing dispositions of curiosity about other people’s experiences, but also educating people how to express their own experiences to diverse social counterparts, and encouraging them to understand their own experiences and activities as part of a diverse social whole. For example, Addams argued that manual laborers in factories deserved education not only in how to work machines, but in the history of the invention of those machines, the uses and distribution of the products they were manufacturing, the finance and sales aspects of the industry, and the indispensability and value of their own labor contributions.

By all accounts, Jane Addams was a great visionary in democratic philosophy. She expanded democracy from its narrow definition as a political structure into an everyday practice that permeated art, social reform, industry, education, and all areas of human interaction. She reimagined democracy as a holistic, encompassing feature of society, drawing people’s minds together through mutual curiosity and empathy. With Addams, democracy became an embodied ethic with which to assess our own behaviors and relationships. Her ideas influenced her pragmatist contemporaries, most notably John Dewey, whose book, Democracy and Education, undoubtedly took much inspiration from Addams’ earlier publication. From Addams’ work, we can also understand how pragmatist theories of democracy evolved from practical encounters with democratic reform efforts and social work among the diverse immigrant neighborhood surrounding Hull House. Any account of pragmatist political theory would be incomplete and significantly impoverished by the exclusion of Addams’ contributions.

About the author:

Parysa Mostajir is a Teaching Fellow in Conceptual and Historical Studies of Science at the University of Chicago. Her research interests include pragmatism, history and philosophy of social science, science and aesthetics, and science and values. Her teaching priorities include (re)diversifying syllabi to include formerly erased or overlooked figures, and encouraging students to apply their education to projects that matter to them.

Parysa Mostajir is a Teaching Fellow in Conceptual and Historical Studies of Science at the University of Chicago. Her research interests include pragmatism, history and philosophy of social science, science and aesthetics, and science and values. Her teaching priorities include (re)diversifying syllabi to include formerly erased or overlooked figures, and encouraging students to apply their education to projects that matter to them.

References:

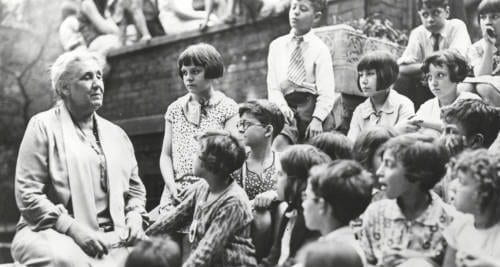

Featured Image: Jane Addams and a group of children at Hull-House, 1933. Photography by Allen, Gordon, Schroeppel and Redlich, Inc. Source: JAMC_0000_0030_0058, Seven Settlement Houses digital image collection, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Illinois at Chicago.

[1] Letter to Richard Theodore Ely, May 18, 1901. Jane Addams Papers Project: https://digital.janeaddams.ramapo.edu/

[2] Mary Jo Deegan. Jane Addams and the Men of the Chicago School, 1892-1918. New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1988, pp. 2, 33.

[3] John Dewey, Lectures, Volume 1: Political Philosophy, Logic, Ethics. Ed. Donald F. Koch. Center for Dewey Studies at Southern Illinois University, 2016, p. 2379.

[4] Jane Dewey, “Biography of John Dewey,” in Paul Arthur Schilpp (ed.), The Philosophy of John Dewey. New York: Tudor Publishing Company, 1958, p. 30.

[5] Letter to Jane Addams, September 17, 1902; Letter to W. I. Thomas, December 27, 1909. Jane Addams Papers Project.

[6] Jane Addams, “Trades Unions and Public Duty,” American Journal of Sociology, 4:4 (1899), p. 460.

[7] Jane Addams, Democracy and Social Ethics. New York, London: The Macmillan Company, 1907, p. 6.

[8] Addams, Democracy and Social Ethics, p. 11.

[9] Addams, Democracy and Social Ethics, p. 7.

[10] Addams, Democracy and Social Ethics, p. 9.

[11] Addams, Democracy and Social Ethics, p. 6.

[12] Addams, Democracy and Social Ethics, p. 5.

[13] Addams, Democracy and Social Ethics, pp. 9-10.

[14] Addams, Democracy and Social Ethics, p. 7.

[15] Addams, Democracy and Social Ethics, p. 34.

[16] Addams, Democracy and Social Ethics, p. 32.

[17] Addams, Democracy and Social Ethics, p. 158.

[18] Addams, Democracy and Social Ethics, p. 144.

[19] Addams, Democracy and Social Ethics, p. 8.

[20] Jane Addams. Twenty Years at Hull-house: With Autobiographical Notes. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1911, p. 436.