By Daniel Yue (Jiayuan Yue) ~

Elizabeth Anscombe was a 20th-century philosopher best known for her work on intention and action theory. Her famous book in this field, Intention, was viewed by Donald Davidson as the most important work on action theory after Aristotle[1]. Anscombe had great influence over many philosophers like Davidson, who later expanded her work and developed the “Davidson-Anscombe Hypothesis” on action and intentions. Anscombe’s work also had clear connections to real social problems. Her discussion of intention was clearly relevant to the historical context of Truman’s use of atomic bombs in World War II and the ethical issues[2]. However, the fame of her work in the field of action theory does not mean she did not face challenges as a female philosopher. In the mid-20th century, her teacher, Wittgenstein, disliked female students with Anscombe being an exception. He called her the “old man” and regarded her as an “honorary male” as if males are more suited for philosophical studies[3].

While Anscombe’s work on intention had a lot of discussions and comprehensive studies, she wrote on a range of subjects much broader than intention and action theory. Many of these works are neglected, especially those that did not have rigorous interlocutions with famous male philosophers[4]. Out of these, two are especially intriguing for their surprising resonance with present-day language studies and psychology, the first-person and the intentionality of sensation.

Anscombe’s discussion of the first person “I” starts by pointing out a problem with Descartes’s famous quote “I think, therefore I am”. What “I” means in this quote is not properly defined. Descartes argues that one can doubt that “I have a body” but not that “I am”. Here Descartes treats “I” in a traditional way as a reference to himself – he is thinking his thoughts so he must exist. Otherwise there is no thinker. However, Anscombe argues that just like Descartes can doubt “I (referring to Descartes) am a body”, he can also doubt that “I am Descartes”[5]. This is quite imaginable – someone is questioning his or her own identity. If “I” is a direct reference to Descartes, then this doubt is the same as doubting “Descartes is Descartes”, which creates a tautology and does not make much sense. This contradiction shows that “I” cannot just be another name that Descartes uses to refer to himself. “I” is not a proper name that has a clear referential relationship with a person.

After arguing that “I” is not a proper name like “John”, Anscombe describes two hypothetical situations to further show that the relationship between “I” and oneself is not a simple reference. The first hypothetical situation is: imagine a small society where people don’t have the names (“Elizabeth”) or pronouns (“I”) as real people do[6]. They only have two special names. One is “A”, which is shared by everyone, written on everyone’s wrists. The other is unique to each person like B-Z but is written on their back so they cannot know that name by themselves. Suppose a person B is describing another person C’s actions, B could see the name of C on his back (“C”) and say “C is doing something …”. When B refers to his own actions, he uses the name on his wrist – A. Everyone refers to their own actions as “A did something …”. They could infer from other people’s descriptions of themselves what their unique name may be, but that inference would always be indirect – they can never directly see their own unique name. The only thing they are certain of is they can refer to themselves as A. The question is: does A equal to “I”? Anscombe answers no. Although A could function in sentences in exactly the same way as “I”, these people don’t connect A to self – they are not self-conscious[7]. They may see the “A” on other people’s wrists and refer to other people as A, not thinking that A is themselves. Real people would never try to describe other people’s actions and say “I am doing something …”. “I” is connected to selfness.

The second hypothetical situation Anscombe describes is simpler. Suppose John loses all his memories in an accident and can no longer identify himself as John. He still retains the ability to use “I”. He does not identify himself with John, but he will never fail to identify himself with “I”[8]. John still has self-consciousness. He does not have a problem thinking about himself. It is the referential relationship between “I” and John that is broken. This is the exact opposite of the last example, where the referential relationship is well-established but there is no self-consciousness.

Finally, Anscombe proposes a two-step process to account for all the examples she described and to explain self-consciousness. Concluding from the examples she described above, Anscombe argues that “I am John” is not an identity proposition, but the result of two identity propositions. She gave a further example to help convey this point. Imagine a wax man at a museum with a sign in front that says “I am a wax man”. Certainly, the wax man does not have self-consciousness, but we have no problem understanding that some staff took the perspective of the wax man to introduce himself[9]. There is a two-step identification taking place here. First, this “I”, though referring to the wax man, identifies with someone else (maybe the staff), and second this someone else identifies with the wax man. Similarly, “I am John” is not a direct identification of “I” with John. Instead, “I” am some other thing, and then this thing is John as if I am something else that borrowed John to speak through him[10]. This explanation handles the examples above very well. “A” as a name does not have such a complex relationship and is just a simple reference, so it does not suggest that A-users are self-conscious. The person who lost all memory can no longer link “this thing” to John but has no problem knowing that “I” am this thing, and hence has no problem using “I” in sentences.

Her work on the first person is important because both her method and her arguments are surprisingly relevant to present-day linguistic studies. Present-day studies of referring expressions like “I” usually find the origin in Kaplan’s “Demonstratives”[11]. In this work, Kaplan lays out the two levels of meanings of “I”. There is a context-invariant layer of meaning – “I” refers to the speaker in discourse. There is also a context-dependent layer of meaning – who the speaker is depends on the context of the conversation. The two layers of meaning are similar to Anscombe’s discussion of the two-step process of the “I” identification. First, “I” identifies with some “thing” or some perspective, and this is like Kaplan’s context-invariant meaning. Second, this “thing” or perspective identifies with some person, and this is like Kaplan’s context-dependent meaning. When we trace the origin of discussions on referring expressions, we should probably not only focus on Kaplan but also include Anscombe in the picture.

Besides the first person, Anscombe’s work also extends to the intentionality of sensation and perception. Her argument stems from a general discussion of “intentional object” and “intentional verbs”, which will later be specified to sensations. Intentional verbs are verbs like “to think of” and “to worship”. Intentional objects are some special objects that have the three features of intention[12]. First, the object could be nonexistent. “The Greeks worshipped Zeus” is true regardless of whether Zeus really exists. Second, the intentional object could be indeterminate. One can “think of a man” without thinking of his height, but a man must have a height in reality, so the thought could miss out on some information. Third, not every true description of the object is true of the intentional object. Suppose John is thinking of a man and the man is six feet tall, it may be wrong to say “John is thinking of a six-foot-tall man” – maybe John doesn’t know his height[13]. Besides the three features of intentional objects, Anscombe emphasizes that “intentional object” is only defined under a grammatical context. “A man” is an intentional object only in the context of discussing the sentence “John is thinking of a man”[14]. What is an intentional object depends on the sentence context.

Regarding the specific topic of sensation, Anscombe first lays out the two traditional explanations of sensation – Russell’s “sense-data” and the ordinary language philosophy. The two theories oppose each other in their positions of what we are immediately aware of in our sensations[15]. Russell’s “sense-data” theory proposes that we are immediately aware of sense-impressions while the ordinary language philosophy proposes that we directly see the objects without any intermediaries like impressions. The two theories have different explanations of phrases like “seeing unicorns” (where unicorns aren’t real). Sense-data theory would explain that we see the impression of unicorns. Ordinary language philosophy explains that we do not actually see anything, but we think we have seen unicorns.

Anscombe offers constructive criticism of both theories by reshaping the role of intention in “seeing”. She points out that in “seeing”, there is always an intentional object and usually a material object. The intentional object has already been defined. The material object is the real thing that is seen. Anscombe points out that ordinary philosophy and sense-data theory oppose each other because neither understood intentionality of perceptions. Ordinary language philosophy only discusses material objects. Sense-data theory seems to hint at some intentionality in the discussion of “impressions” but failed to tell it apart from material objects. Anscombe’s theory resolves this dispute by introducing the concept of the intentional object. “Seeing” always has an intentional object, but does not always have a material object[16].

This criticism is constructive because it incorporates and recognizes many sharp observations made by philosophers on both sides of the debate. For example, the comment “you can’t have seen a unicorn. Unicorns don’t exist.” is discussed by the ordinary language philosophy that the lack of a material object “unicorn” falsifies “seeing a unicorn”. Anscombe acknowledges the importance of this example and reinterprets it with one of the features of intentional objects – that the intentional object “unicorn” may not have a real material object[17]. On the other hand, she also appreciates the sense-data theory. Suppose one sees an image that appears very shortly and cannot see its color, but there still must be a visual impression of its color. If this person is asked “what color did you see”, the answer would be “I am not sure” but could never be “what color? I didn’t see color”. Anscombe reinterprets this example with the indeterminacy feature of intentional objects – the material object must have a color but that’s unnecessary in the description of the intentional object[18]. Finally, Anscombe provided some more evidence for her own argument that sometimes “seeing” has both intentional and material objects and sometimes only intentional. Imagine that “I saw a man born in Jerusalem”. There is no way I could have seen him actually “born” as an intentional object, but this description is only true for the material object beyond my sensations. Here “saw” has both intentional and material objects[19]. Then imagine me speaking to a doctor about seeing “floating specks before my eyes” and the doctor explains why medically. Of course I know the floating specks cannot be real material objects, but I do still see them. Here “seeing” does not have material objects and only intentional objects[20].

Combining the two subfields of work, we can see both the internal and external importance of these neglected works of Anscombe’s. Internally, these works on the first person and sensation are integral parts of Anscombe’s philosophy. Especially for sensations, “seeing” is discussed in such a similar way to “intending” or “thinking of”, connecting sensation to Anscombe’s most famous work on intention. These works on self-consciousness and the intentionality of sensation are coherent with Anscombe’s greater discussion of human actions. Externally, we have come across numerous philosophers that these works engage with. The first person criticizes Descartes. The intentionality of sensation discusses Russell, ordinary language philosophers, and refers to Austin’s ideas as well. According to Teichmann’s accounts, these essays are also aimed at criticizing the philosophy of phenomenology[21]. In her other works on the same field, she offers new definitions for concepts like perception. Besides philosophy, these works also resonate with linguistics and psychology. The first person’s redefinition of pronouns and indexicality are important topics of present-day linguistic studies of meaning. The intentionality of sensation is echoed by a lot of present-day psychological studies of how perception is not a passive process but an active process of constructions that brings in the subjectivity of the perceiver. In these ways, the neglected works of Anscombe have proven to be valuable and insightful.

About Daniel Yue (Jiayuan Yue):

I am a second-year student at the University of Chicago, majoring in linguistics and psychology. I grew up in Shanghai, China, and came to the US for my college education. In these environments, my experience and exposure to Chinese, English, and various dialects like Shanghainese have greatly fostered my interest in the study of language, both by itself and in relation to culture and societies. In the process of writing this blog post, I learned about some important ideas and figures in the philosophy of language and linguistic philosophy, and I hope to share my understanding of the great value of women’s contributions in this field. My understanding must have some inaccuracies and mistakes, and I will continue learning and correcting them. In my free time, I like playing and watching tennis and football (the one played with foot), though sadly I am good at neither of them.

References:

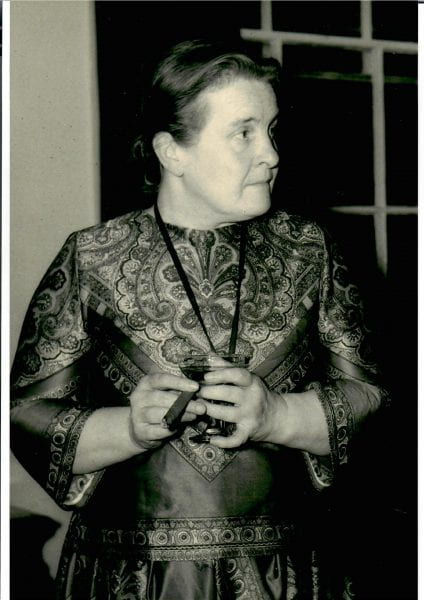

Featured Image: Courtesy of The Anscombe Bioethics Centre, 82–83 St Aldate’s, Oxford OX1 1RA, United Kingdom

[1] Rachael Wiseman. “GEM Anscombe.” Oxford Bibliographies, 11 Jan 2017

[2] Julia Driver, “Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2018)

[3] Driver, “Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe”

[4] Wiseman, “GEM Anscombe.”

[5] GEM Anscombe. The First Person. In Mind and Language, 1975, p.22

[6] Anscombe, The First Person, p.24

[7] Anscombe, The First Person, p.25

[8] Anscombe, The First Person, p.33

[9] Anscombe, The First Person, p.25

[10] Anscombe, The First Person, p.33

[11] David Kaplan. Demonstratives. 1977.

[12] GEM Anscombe. The Intentionality of Sensation: A Grammatical Feature. Blackwell, 1965, p.56

[13] Anscombe, The Intentionality of Sensation, p.57-58

[14] Anscombe, The Intentionality of Sensation, p.61-62

[15] Anscombe, The Intentionality of Sensation, p.64-65

[16] Anscombe, The Intentionality of Sensation, p.71

[17] Anscombe, The Intentionality of Sensation, p.67

[18] Anscombe, The Intentionality of Sensation, p.69

[19] Anscombe, The Intentionality of Sensation, p.71

[20] Anscombe, The Intentionality of Sensation, p.73

[21] Roger Teichmann. The Philosophy of Elizabeth Anscombe. Oxford UP, 2008, p.128